Σ.Ε.Κ.Α. Victoria

The Justice for Cyprus Co-ordinating Committee, Webmaster: Pavlos Andronikos

The Justice for Cyprus Co-ordinating Committee, Webmaster: Pavlos Andronikos

Turkish troops invaded Cyprus on 20 July 1974, five days after the government of the island was toppled by a military coup engineered by the US-sponsored junta then ruling Greece. This gave Turkey the pretext to invade for which she had been waiting since at least 1963.

The invasion, it was claimed, was to protect the Turkish Cypriots;[1] and to legitimise its aggression Turkey cited the 1960 Treaty of Guarantee.[2]

The international reaction was muted. Propaganda throughout the 50s and 60s had painted the Greek Cypriots in the blackest of colours, and Turkey’s military action was seen by many as having some justification.[3]

With the 2nd invasion of 14 August, however, a shocked world realised that the Turkish army had no intention of restoring constitutional order to the Republic of Cyprus, and that its aim was in reality to partition the island.

It should be noted that by imposing partition, Turkey violated the Treaty of Guarantee in its entirety, for the Treaty was created and agreed to by Britain, Greece, and Turkey specifically in order to rule out partition and enosis, and it expressly prohibits “partition of the Island”.[4]

In the initial invasion, Turkish forces captured only 3% of Cyprus before being compelled to accept a ceasefire. Three weeks after the ceasefire, and despite the fact that an agreement in Geneva seemed imminent, the Turkish army mounted its second full-scale offensive. This began within hours of the Turkish delegation’s refusal to grant the Greek Cypriot acting president Clerides a 36 hour break to consult with all parties before responding to Turkey’s demand for a federation.

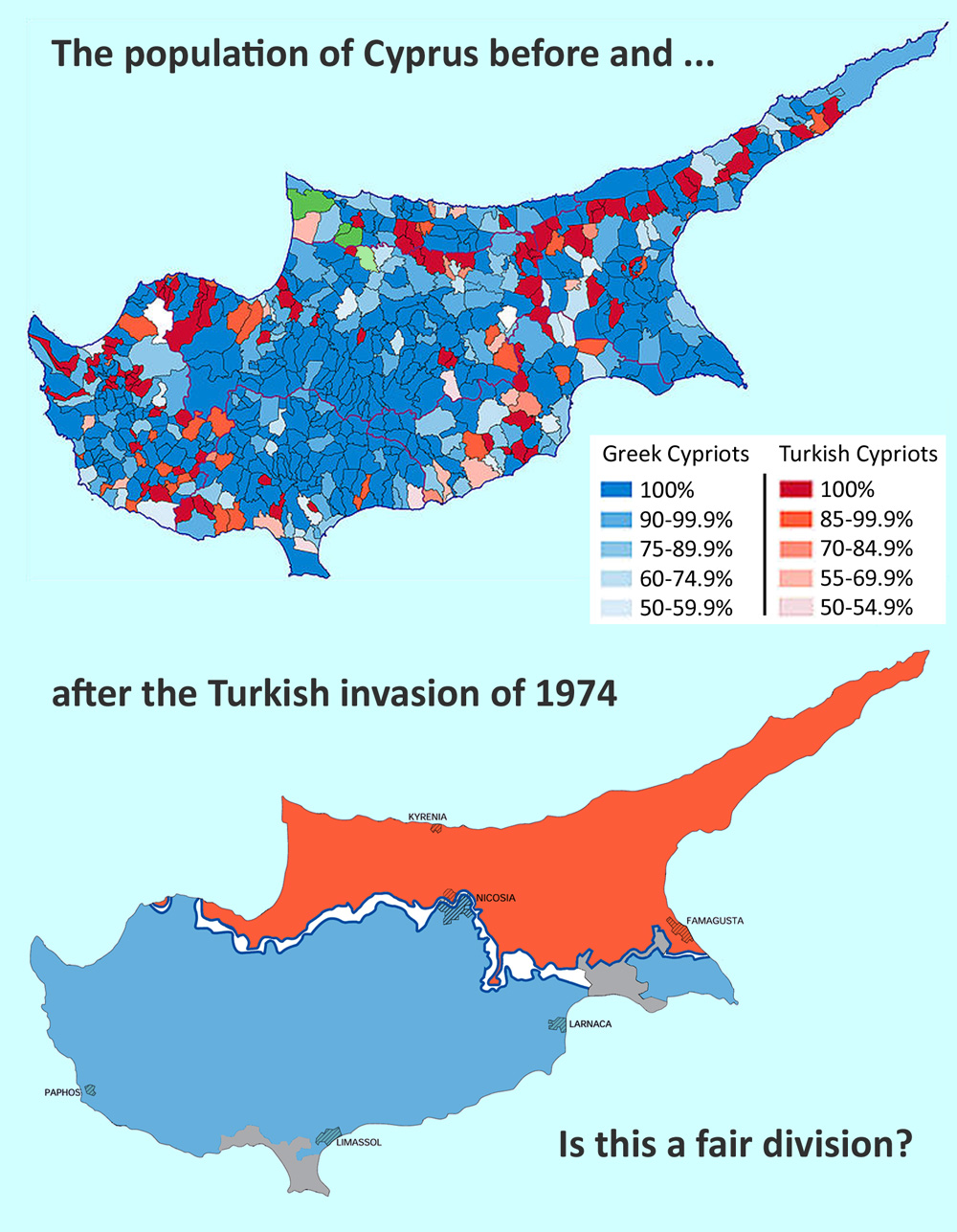

As a result of the second offensive, almost 37% of the territory of the Republic of Cyprus fell to the Turkish military, and nearly one third of the population, some 164,000 Greek Cypriots, were forcibly uprooted from their homes and villages.[5] In fact, more Greek Cypriots became refugees, than the total number of Turkish Cypriots on the island.

As was realised when the Greek Cypriot refugees were not allowed to return to their homes, Turkey had expertly ethnically “cleansed” a massive area in the north of the island.

More than four decades later, the legitimate Greek Cypriot inhabitants, who constituted a majority in the occupied territory, have still not been allowed to return to their towns and villages, and the Turkish Army is still occupying 37% of Cyprus despite UN resolutions calling for its withdrawal. To make matters worse, Turkey has engaged in a huge and unlawful programme of colonisation and Turkification of the occupied territory. There are now anything from 175,000 to 250,000 illegal Turkish settlers in Cyprus, in contravention of the Geneva Convention.[6]

Varosi, Famagusta

One particularly shocking result of the 2nd invasion was the capture of Varosi, the modern section of Famagusta and Cyprus’ equivalent of the French Riviera. As the Turkish Army and the TMT terrorists pushed eastwards across Cyprus, they left behind them a bloody trail of indiscriminate murder and rape. Presumably the thrill of violence was a factor in their treatment of the Greek Cypriots they captured, but they also had a strategic aim—to scare the Greek inhabitants in their path and cause the bulk of them to flee to safety before this terror.

Thus, when the Turkish military got to Famagusta, they found Varosi almost completely emptied of its inhabitants, and they claimed it for themselves. There was no justification for this. None at all. Most of the Turkish Cypriots of Famagusta lived in the walled old city which lies to the north of Varosi. They could easily have partitioned off the old city and let Varosi be. Their capture of it was an act of greed and bloodymindedness.

It was because of this that the United Nations Security Council insisted in its rulings that Varosi must be returned to its inhabitants.[7] Forbidden from settling their own people in the town, the Turks simply fenced off the main and central part of Varosi where the prime beach and the luxury hotels were, and let it stand empty for decades—a ghost town. A more vindictive and spiteful stance is hard to imagine.

Pavlos Andronikos

Following the Turkish invasion, Cyprus has come to be seen, erroneously, as made up of a Greek South Cyprus and a Turkish Northern Cyprus. However it is wrong to identify the northern part of Cyprus which is currently occupied by the Turkish Army as Turkish, and equally wrong to identify the south as solely Greek. Prior to the Turkish invasion there was no large area of Cyprus that was purely Turkish or Greek. There were Greek and Turkish villages, as well as mixed villages, scattered all over the island, but overall the Greeks were in the majority. The Turkish invasion created an anomalous demographic state of affairs which has yet to be rectified.