Σ.Ε.Κ.Α. Victoria

The Justice for Cyprus Co-ordinating Committee, Webmaster: Pavlos Andronikos

The Justice for Cyprus Co-ordinating Committee, Webmaster: Pavlos Andronikos

by Pavlos Andronikos

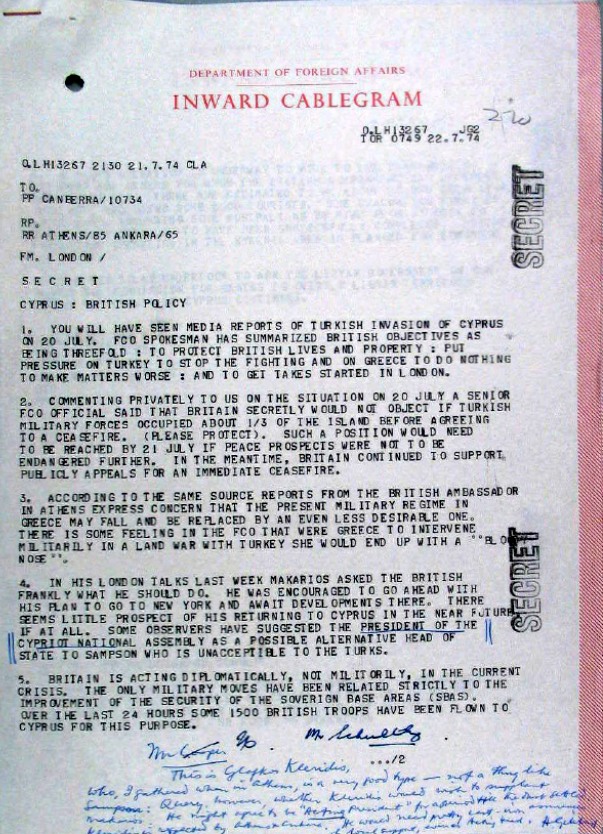

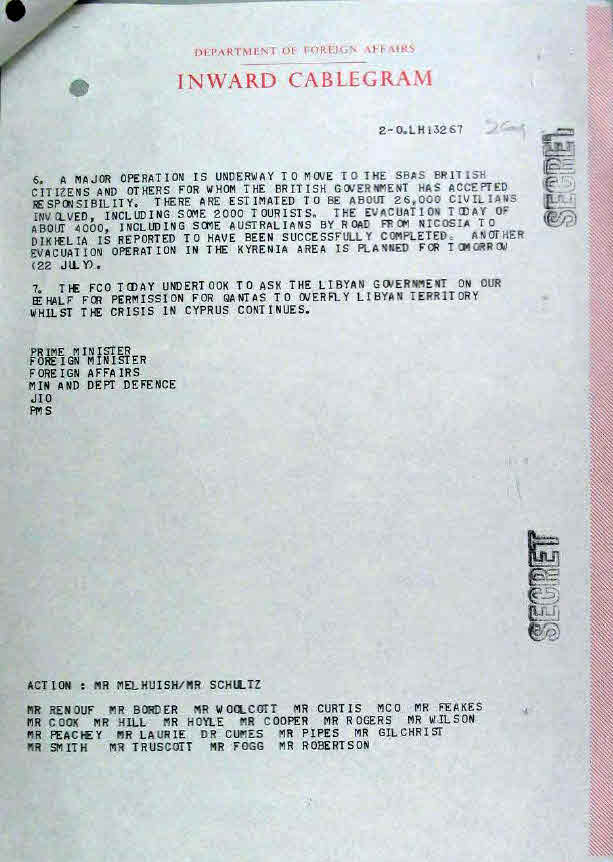

The telegram below was sent by the Australian High Commission in the UK to Australian Government officials on the 21st of July 1974 at 9.30 p.m. London time. It outlines British aims and objectives, and reveals that secretly Britain is prepared to accept the occupation by the Turkish Army of one third of Cyprus, i.e., a de facto partition of the island.

This despite the fact that the UK was a signatory to the Treaty of Guarantee and was supposed to “guarantee the independence, territorial integrity and security of the Republic of Cyprus”.

The Treaty of Guarantee expressly prohibits “any activity aimed at promoting, directly or indirectly, either union of Cyprus with any other State, or partition of the Island”.

QUOTE from the Telegram: “Commenting privately to us on the situation on 20 July a senior FCO official [Foreign and Commonwealth Office] said that Britain secretly would not object if Turkish military forces occupied about 1/3 of the island before agreeing to a ceasefire.”

Note that in 1974, Australia was a non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council.

The handwritten annotation:

This is Glafkos Klerides who, I gathered when in Athens, is a very good type–not a thing [or ?thug] like

Sampson. Query, however, whether Klerides would wish to supplant Makarios. He might agree to be

“Acting President” for a period till the dust settled. Kleridis is respected by Athens and Ankara.

He would need pretty cast-iron assurances of local support, even as Acting Head.

[signed] H. Gilchrist

The telegram above was discovered by George Kazamias, who wrote an article based on it with the title: “From Pragmatism to Idealism to Failure: Britain in the Cyprus Crisis of 1974” (GreeSE – Hellenic Observatory Papers on Greece and Southeast Europe 42, Hellenic Observatory, LSE, 2019).

On the one hand, George Kazamias acknowledges that the Australian telegram he discovered offers a level of information beyond what is usually found in the diplomatic archives which are released to public access, but on the other hand he chooses not to contemplate the possibility that there may be more incriminatory material waiting to be discovered at that most secretive of levels.

Thus he states that: “The text of the Australian telegram seems to offer us a glimpse into a level of policy that is seldom allowed to see the light of day (at least not a ‘mere’ 35-odd years from the event)…”; and acknowledges that: “Compared against existing knowledge, this telegram appears to give us a very different view of British policy in July 1974.”

But then he states that: “Τhe author of this paper does not subscribe to conspiracy theories; thus we do not interpret the reference in the telegram to ‘1/3 of the island before agreeing to a ceasefire’ as an expression of a British aim.”

To exclude the possibility that partition was indeed an agreed or a desired aim, seems hasty. And to regard conspiracies as a purely imaginary phenomenon is as irrational as the converse tendency to see them everywhere. They can and do happen, sometimes.

What is certain is that the remarkable continuity between George Ball’s assertion to Martin Packard in 1964 that “our plan here is for partition”, and the imposition of partition in 1974, apparently with the UK’s secret acquiescence, needs to be explained. (See Martin Packard, Getting It Wrong: Fragments from a Cyprus Diary, 1964 [AuthorHouse, 2008].)

Pavlos Andronikos