Σ.Ε.Κ.Α. Victoria

The Justice for Cyprus Co-ordinating Committee, Webmaster: Pavlos Andronikos

The Justice for Cyprus Co-ordinating Committee, Webmaster: Pavlos Andronikos

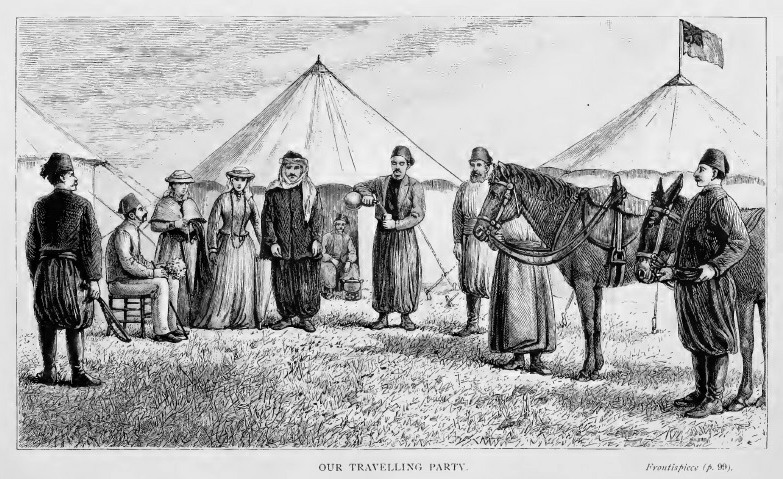

An Excerpt from the book Through Cyprus by Agnes Smith, 1887 |

|

The Scottish twin sisters Agnes Smith Lewis (1843-1926) and Margaret Gibson (1843-1920), heiresses of an extremely wealthy man, between them learned numerous languages, including modern Greek, Arabic, Hebrew, Persian and Syriac, and became pioneering biblical scholars and explorers at a time when women rarely ventured alone to foreign lands.

In 1887 Agnes Smith Lewis published an invaluable account of their exploration of Cyprus under British rule. Her comments at the conclusion of the book about what the future might hold for Cyprus make fascinating reading and are deeply poignant given the troubled history of the island since the 1950s.

pp. 320-321

No one dreams that it [Cyprus] will ever be given back to Turkey. The hands on the clock of Time cannot thus be put back, the islanders, however ungrateful they may eventually prove, can never be consigned to that oppressive rule. To do so would be to tarnish the scutcheon of British honour; it would be a libel on Christianity itself. So much is certain. If we do not keep it ourselves, we must resign it to some other western Power, or to Greece.

We cannot of course do the former; for we can permit no possible rival to plant herself in the path of our march to and from Cathay. Let us examine what chance there is of the latter.

The Greeks have no right to Cyprus, say some. We agree with their verdict, but not at all with their reasons. Greece never had Cyprus, that is true, but it is stretching a point beyond the bounds of truth to say that her population is not in the main Hellenic. For what constitutes nationality? Blood and language, which are strongest in their ties if woven closer by a common religion.

The population of Cyprus is of course mixed. One fourth is avowedly Turkish, and the remainder must undoubtedly have received many contributions from Semitic and European sources. But the main stream of Hellenism has absorbed these; the spoken dialect alone being sufficient to prove that the island has been substantially Greek since the time when history began to be written. The dialect is of course not pure. No academy nor common school has kept it free from corrupting elements. The influence of Venetian and of Turk has been employed to overpower it, but for that very reason its evidence in favour of the nationality of the peasants who speak it is the more unimpeachable and convincing.

pp. 323-340

Do the majority of the islanders wish to be annexed to Greece? We cannot answer this question, but we think it probable that they are not yet sufficiently well educated to formulate their wishes. The ancient Cypriot earned through his ignorance the epithet of βους Κύπριος, being equivalent to υς Βοιωτία; [1] and the natives of Lapithus were so superlatively stupid that λαπάθιον meant a fool. The modern Cypriot is not so stupid as he is taken to be by the people of Beyrout, who, when anyone tries to over-reach or to bamboozle them, are wont to ask,

‘Do you take me for a Cypriot?’

He has, above all, an eye to the main chance. He is industrious and thrifty, and he will be able to judge as to whose rule will best further his worldly interests. But let us not deceive ourselves. This state of mind will last so long as he cannot read the newspapers. What then?

Some day he will read Greek ones. Whether or not he wishes for incorporation in the kingdom of King George, there is no question as to whether King George’s subjects want him. Athenian newspapers, whenever they deign to specify what they mean by the expression: η δούλη Ελλάς, ‘enslaved Greece,’ enumerate Epirus, Macedonia, the islands, and Cyprus. So fervent are their aspirations for its acquisition, that I have heard an Evangelical missionary in Constantinople, though himself an Englishman, when leading the devotions of a Greek congregation, pray for the enfranchisement of this part of his own sovereign’s dominions.

I have in my hands a book lately published by a Cypriot, entitled: ‘A Manual of the Topography and General History of Cyprus.’[2] Perhaps my readers would like to hear what he says on this subject:

‘Cyprus,’ these are his words, ‘suffered much, and was very wretched during this last historical period (i.e., under Turkish rule). The only thing that has remained unimpaired and unsettled by these terrible afflictions is her national and religious consciousness. Neither under the Franks nor under the Turks was the Cypriot shaken in the principles he held about his faith and his fatherland. The imperfect schools of that epoch recalled to him memories of the great Past; and the poor churches in which he found a momentary consolation introduced him to a horizon of the Christian and the avenging future. He preserved his language uncorrupted; he remained in the faith of his forefathers; he was hung; he was cut to pieces; he was impaled, but he did not abjure it; he was broken, but he was not bent, and, whilst being slaughtered, he did not curse his tormentors. Marcello Cerrutti, a distinguished Italian, formerly an ambassador, now a senator, who had studied the Cypriots closely, characterized them truly when he said to me a few years ago in Rome: “Cyprus is the noblest aspect of Hellenism.” (“Cipro è la piu nobile fisionomia del grecismo.”)[3]

The tendency of Cyprus towards decline and desolation dates chiefly from the end of the twelfth century, after the Christian era. Then conquerors, who were strangers in race, in religion, and in language, began succeeding each other until the present day. What greater proof can we have that a foreign domination is a veritable gangrene in every respect to peoples, and that, where there exists no connecting link in the identity of interests and of aims, there is no effective mutual guarantee betwixt rulers and ruled? There is no legal, political contract which is just to both; everything is phenomenal; and whatever is really profitable, permanently progressive, and thoroughly salutary, is never begun sincerely, or, if it is begun, it does not take root. Rather, on the contrary, all measures taken by the rulers, either intentionally or through ignorance, contain the germs of some kind of dissolution, material or otherwise. In one word, foreign dominations, even the most tolerable and tolerant of them, the most gentle and the most scrupulous in the fulfilment of their promises, are always step-mothers, never mothers. Let us hope that the period of adopted mothers, at least so far as concerns Cyprus, is now fulfilled. The true nurse, the genuine mother, who has long been thrust aside, who has been considered dead, but whose death was only apparent, has grown strong and has risen from her bed, and gathers round her, one by one, her wandering offspring. First there came to her the venerable group of the Ionian islands, and then followed other renowned seats of primordial Hellenism. Cyprus to-day, to-morrow, at some hour by no means distant, will also come skipping and leaping, like a fawn, to the national flock, in order that she maybe cleansed from the stain of servitude, and then clothed in her festive raiment, with those of her own blood who have been already redeemed, and those who shall be redeemed in the future, she will enter on the laborious struggle for civilization; the struggle bequeathed to her by her forefathers, those incomparable pioneers of humanity under its manifold phases.’

The same writer says, in another place:

‘Massimo D’Azeglio, the distinguished Italian politician, said, a few years before the war of 1859 against Austria, when he was a prey to incurable and sinister apprehensions:

‘ “Italian unity is the first of my wishes, and the best of my hopes.” We, who are the interpreters of our own sentiments no less than of those of our compatriots, have not the least hesitation in expressing this optimist opinion: “The annexation of Cyprus to Greece constitutes the first wish of the Cypriots and the first of their hopes.” ’

On another page he tells us of the delightful excitement which was produced in the island by the news of the cession, how the price of horses and of land rose threefold, and how unaffected joy took possession of every heart, ‘because that day marked the setting of a three-centuries’ tyranny, and the rise of a new life; the bait of the unknown had ensnared everyone; they did not shut their eyes to the fact that it was a simple shifting of their yoke, but they, nevertheless, made a distinction between a Christian xenocracy and an anti-Christian one. In short, notwithstanding some stings of national pride, public opinion was in a state of high expectation. But, ere many days had elapsed, a distinguished Maltese merchant, who had landed some goods beyond the space assigned for disembarkments, was condemned to be beaten with forty strokes. Thus was given, at the very first blush, the measure of the liberties brought by the new foreign government, and the circumstance awakened the most painful reflections. “How is this?” asked the Cypriots. Corporal punishment, the cherished system of the Ottoman despotism, the system which recalls to us the saddest days of slavery, the system of which such a harsh use and abuse was made in Cyprus until the year 1850, is it to be again disinterred and placed in the orders of the day by the sworn champions and standard-bearers of human civilization and political liberty?” So the error was but for a moment, and, ever since, the feeling of the place, unanimous and unshaken, has been more national than ever, and the mind of every Cypriot who is in the slightest degree freed from the feeling of servitude, turns eagerly, not towards deceitful appearances, but towards the far-shining and ever-brilliant light of a national guidance.’

Again, he says:

‘The nominal and mouldering titles of the Caliph disturb very little the golden dreams in which the joyful Cypriots indulge. They, if they love the dominion of the English, a dominion which is defective in many things and sometimes devoid of love, do so in consequence of the idea which is firmly rooted in our consciousness, that it is necessarily transient, and will turn out to be the bridge designed by Destiny for our transfer to the beloved and classic land, which has fostered us, cradled us by never-to-be-forgotten lullabys, and held a torch to us when we wandered in darkness and in the shadow of death; to her from whose simple name there flowed strength in unceasing danger, consolation in times of calamity, promises about a common future, about a day of restoration, of which the dawn appears already on the horizon, cloudless and rosy, darting its first beams over the summit of the Cyprian Olympus. No, these are not winged words; it is sufficient that we show clearly the undoubted right which we possess of protesting by every lawful method against those who consider us as merchandise or as a flock of sheep, always ready to be sold, without strength or will, forgetful of all the past and of the teachings of history, insensible to national disgrace, blind to the obvious and humiliating reality, to the signs of the times, to the manly attitude of other peoples, and culpably irreverent towards the holiest and noblest traditions.’

This, some of my readers will say, is simple rhodomontade. But, nevertheless, we shall be judicially blind if we do not take some account of the feeling it expresses. Sentiment governs the world more powerfully than some people suppose.

We need not fear that the Greeks will ever be able to wrest Cyprus from us. But they have before them the precedent of the Ionian islands, and they may succeed in making our rule unpopular, and in getting up an agitation which would be disagreeable to us and injurious to their own best interests. How are we to prevent this?

By ceasing to encourage education? Such a course would be most unworthy of us, and impossible in the light of nineteenth-century progress. By encouraging an immigration of Arabs? I blush to say that I have heard this seriously proposed; but, in justice to my fellow-countrymen, I must add that it was by a man who knew nothing whatever of the island. Only two methods commend themselves to me, and there is no reason why they should not go hand in hand. The first is, to encourage the settlement of English families, and the second, to place ourselves in sympathy with the islanders by endeavouring at least to understand Hellenic aspirations.

Sir Samuel Baker says that ‘one of the most urgent necessities is the instruction of the people of Cyprus in English, because it is not to be expected that any close affinity can exist between the governing class and the governed in the darkness of two foreign tongues that require a third person for their enlightenment. The natives dread the interpreter; they know full well that one word misunderstood may alter the bearing of their case, and they believe that a little gold judicially applied may exert a peculiar grammatical influence upon the parts of speech of the dragoman which directly affects their interests. It cannot be expected that the English officials are to receive a miraculous gift of fiery tongues, and to address their temporary subjects in Turkish and in Greek; but it is highly important that without delay schools should be established throughout the island for the instruction of the young, who in two or three years will obtain a knowledge of English. Whenever the people shall understand our language, they will assimilate with our customs and ideas, and they will feel themselves a portion of our empire; but until then a void will exclude them from social intercourse with their English rulers, and they will naturally gravitate towards Greece through the simple medium of a mother tongue.’ (pp. 409, 410.)

Some of these words are golden, and we have Mrs. Scott Stevenson’s evidence for the fact that the natives were in 1880 cruelly defrauded by a lying interpreter.

We would ask respectfully, Are a handful of English officials to do in a few years what the sociable Frenchman and the super-subtle Venetian, during a domination of three centuries, failed to accomplish? Are they to change the spoken tongue of a people? The English in Cyprus are the sons of gentlemen, whose ancestors have for many generations enjoyed the advantages of culture. Is it reasonable to suppose that they are inferior in intellectual power or in capacity for acquisition to the sons of men whose minds have for ages and ages been all but dormant? We may indeed wonder that the Cypriot is not quite brutalised, considering the kind of masters he has had. Is it quite impossible for Englishmen to speak Greek?

We fear the fault must be sought for in our public schools. Our conjecture may be rash, for we have had no experience of these, and are quite ignorant of the systems pursued there. But we judge by the results. Why are English boys, who can construe the prose of ancient authors and imitate their poetry, so totally at a loss when they need to employ a foreign tongue for the common necessities of life? We have an old-fashioned belief that languages were meant, in the first place, to be spoken. Had writing been the chief consideration, they would assuredly have been called calamus and γραφίς, not lingua and γλώσσα. The ear never forgets sounds or phrases with which it has become familiar, the eye often does. A girl may not open a French book for years after she has left school, but she will not forget it as her brother will Latin. And it seems to me that a thorough reform in our teaching is needed, especially in our teaching of Greek.

But how can this reform be brought about? How can Greek become to us what it is to our Cypriot fellow-subjects, a living language, whilst our university professors persist in their present pronunciation of it? That pronunciation was first introduced by Erasmus, but we cannot believe that it would have been adopted had not the true Greek sounds and the true Greek accent been forgotten, owing to the slightness of our intercourse with the natives. We can more readily conceive how this took place with Greek than with Latin, because, so long as the English Church remained in communion with that of Rome, Greek priests cannot have been welcome guests on our shores. Modern Greek may in a few instances, notably in those of η and of the aspirates, come short of what it was in ancient days, but we submit that no other pronunciation places the language in full harmony with those tongues which have been more or less developed from it, or explains so clearly the changes which human speech has undergone.

Take, as an instance, the diphthongs, and see what they become in Latin,—in Latin, I mean, which is pronounced as the Italians, and all nations of the world, except ourselves, believe that it should be pronounced. How naturally, then, do the sounds of the one tongue slip into those of the other! Οίνος once spelt Fοίνος with the digamma, becomes vinum, λείβω and λοιβή pass into libo, whilst lito is apparently related to λειτουργία, and νείφω and νίφω to nivus. Νείλος becomes Nilus, and πειρατής, pirata.

But the case is stronger when we turn to the transliteration of proper names. Naturally, if a Roman author wished to make his countrymen understand how the Greeks pronounced these, he employed those letters which represented the same sounds in Latin. How comes it then that the Greek diphthong οι always becomes in Latin oe, and that αι becomes ae. Βοιωτία becomes Boeotia, Μαίανδρος Maeander, Μαιώτις Maeotis. And as a further defence of itticism, we would mention two instances in which Homer writes δοίο, instead of δύο, viz., in Iliad iii., 236, and xxiv. 648. Ου, pronounced oo in modern Greek, becomes u in Latin. Thus Θουκυδίδης Thucydides.

Ευ was undoubtedly ef, if we may trust the ΒασιλεFς of the inscriptions. But we do not intend to go deeply into this question. We only wish to indicate that those teachers who adhere to an erroneous pronunciation are doing much to unfit their pupils from becoming good linguists.

I am more and more convinced, for my own part, that no language helps its possessor in the acquirement of other tongues as Greek does. Those whose mother-tongue it is are more likely to be polyglots than are Englishmen or Frenchmen, and the light it casts on other European languages is simply wonderful. When pronounced properly, the βούλεσθε (voolesthe) of the Greek passes readily into the voulez-vous of the French, and so on in a thousand other instances. Its grammar is as methodical and offers as good a training to the mind as the Latin one, and its unrivalled flexibility gives to the mind (and perhaps to the organs of speech) a versatility which could not be acquired by years of poring over the written page; and which makes the acquisition of other tongues, even of Semitic ones, comparatively easy. It is commonly said that Greek has no affinity with Arabic. Nor has it, so far as mere words are concerned. To say that there is any resemblance in the two grammars would be to make the hair of a philologist stand on end. Yet, if we accustom ourselves to talk both languages, we will find subtle analogies between the two which point to a similarity in the modes of thought of the peoples who use them, and which greatly facilitate our speech in either.

The plan of learning a language by trying to speak it from the very beginning of our study, has such advantages that one wonders why any other is ever pursued. It obviously excludes cram, because the pupil’s mind at once assimilates or digests its daily lesson. And, if we may judge from our own experience, a student will make more rapid progress in conversation if he will do his best to talk with one of his fellows who is on the same level as himself, and who also wishes to master the art of speaking, than with a native of the country whose patience is put to a severe trial, and who is probably more anxious to learn English than to impart a knowledge of his own tongue. When the student has already acquired some facility in the language, intercourse with natives will be found more advantageous than at the beginning.

It ought not to be difficult for Englishmen to speak Greek. Turkish and Arabic we may excuse them, but the tongue in which the New Testament was written, the tongue which lends of its treasures for the formation of all new scientific and technical words, and which enters so much into the structure of our own language, is surely attractive enough to make its cultivation a labour of love. But if we cram boys with it before they have entered on their teens, before they are capable of appreciating the beauties of English literature, and burden their memories with a host of other things at the same time, what wonder if it appear to most of them as a heap of dry bones?

Far better would it be if we could teach children first the rudiments of Latin, then some modern language, such as French or German, conversationally, and leave the study of Greek till an age when its value would be appreciated. One of the greatest charms of Homer is his naivete, and can this quality be discerned by a boy who is as yet ignorant of the more laboured masterpieces of literature?

So much for the Greek language. I have said that we should seek also to understand our Cypriot fellow-subjects, by placing ourselves in sympathy with modern Greek aspirations. It has become too much the fashion with a certain section of our fellow-countrymen to sneer at these. True, we sometimes meet with boasting and bombast which are in ludicrous contradiction to the realities. True, the direction of affairs at Athens may again fall into the hands of an incompetent politician, who cares not how he wounds the just susceptibilities of the Great Powers, and relies too much on the fact that these Powers are the virtual protectors of his country. We cannot undertake to say that our government was wrong when it joined in the blockade of the Greek ports; although, possibly, it was simply playing the game of Austria. The time for war was then inopportune. But we do say that Englishmen ought to realize a little better the position in which the Greeks find themselves. The greater part of the nation is not yet free. The age of massacres and of fierce oppression may be past, but still the Christians of Turkey are condemned to pay heavy taxes, for which they get no corresponding benefit in the way of protection, or in the supply of many things which are now absolute necessities in civilized life. Foreigners may talk of Turkish enlightenment and of Turkish tolerance, when they have themselves got some valuable concession for making a railway; but the very fact of their having to place themselves under the protection of their own government proves that they cannot trust to Turkish justice.

How long is this state of things to last? How long are four millions of Turks to rule over thirty two millions of other people? most of whom are their superiors in all those qualities which constitute man superior to the brutes. How long are they to clog the wheels of progress by their vis inertiae?

And the rulers of Turkey are now hardly Turks. They are, with few exceptions, the sons of Greek and Armenian mothers; or, worse still, they are members of the subject races who have embraced Islam. They are mostly adventurers, who have attained to high position by the exercise of their wits. Turkish rule, in our eyes, is now a vast system of legalised iniquity. The way in which it degrades women is simply intolerable.

No one doubts that it would not last were it not for the greed of some European powers, and for the jealousy of others. In the natural course of things, it would long since have been swept away. Can we wonder at the Greeks being restless? Englishmen would be equally so, if placed in similar circumstances.

Let us consider the spectacle. We see the little Greek kingdom, not always conducting itself with discretion as regards foreign affairs, with a parliament which too often exhibits the vices inherent in ultra-democracy. But its internal affairs are well managed. Within its bounds there is perfect security for life and property. Schools, posts, telegraphs are everywhere under government management. Then let us turn to Turkey. Her people are heavily and unjustly taxed, yet they have no roads, no security, no native post-office. Stand on the outskirts of Constantinople, and, far as the eye can reach, you will not see an inhabited house, for none outside the city would be safe from robbers. The shopkeepers of Pera, despairing of protection from the police, have engaged a number of ‘hammals,’ or porters, to walk about the streets all night, and show that they are awake and watchful by rapping on the pavement. These men have been known to club together and rob their employers. If you wish to ride for a few miles inland, on either side of the Bosphorus, no consul will guarantee your safety without a doubtfully trustworthy escort.

And you can hardly do so in spring-time without sinking knee-deep in mud. The civil servants of the Ottoman empire are sometimes prevented from going to their offices, because they cannot pay the cost of transit. The soldiers are supposed, in time of war, to live by rapine. I wish those who extol the Turk at the expense of the Greek, would ask themselves a few questions. Why does not a foreigner resident in Athens ask the government of his own country to protect him by capitulations? Why does he try to create no consular court? and why, in every part of Greece is he contented to receive his letters through a native post-office? Surely the Greeks must be a little more trustworthy as a nation than the much-lauded Turks.

A case in point occurs to us. We happened, on our homeward voyage, to meet with a young Jewish merchant from Salonica.

‘What is your nationality?’ we asked him.

‘I am a Turk, but my eldest brother is an Englishman, and my youngest an Italian.’

‘How is that? Are they your half-brothers?’

‘No; it is for our business. If we have a lawsuit, the native courts favour our firm for my sake. If the law-suit is with an Italian, my youngest brother seeks the help of the Italian consul, and if it is with an Englishman my eldest brother represents us.’

‘Are you contented under Turkish rule?’

‘The present system is favourable to us. We have got accustomed to it, and we wish for no change. If the Greeks come, we shall not like it, but we shall remain. If the Austrians come’ (with a shrug of his shoulders), ‘we must seek a home elsewhere; the world is wide enough. The Austrians are very harsh. Les Autrichiens sont durs, bien durs. I cannot see what advantage would accrue to Great Britain through Austria getting Salonica.’

Greeks and Moslems get on pleasantly enough when they live together in the same community. But in the cities the Greeks and the Jews must be like new wine seeking to burst through old bottles. Their intercourse with Europe makes them keenly alive to what civilization is, and they feel it hard to be debarred from its blessings. In the more remote districts they suffer in their feelings, if not in their purses, from the undisguised contempt of their Moslem fellow-citizens.

The sight of Greek women in Turkish harems must be peculiarly galling to their fellow-countrymen. Many of these are the daughters of mothers taken captive after the massacres of Chios. They may have been educated to Moslem habits of thought, but that is of itself a degradation.

The whole current of forces, moral and intellectual, is now strongly set against this state of things. And why should ours be the ungrateful task to stem it?

But the Eastern Christians, say some, are no better than the Turks. This may be so in individual cases, and there is no hiding the fact that the former still persist in the image or idol worship which brought the scourge of the False Prophet on the backs of their forefathers. But the Greek Church has life in it, for it still looks to the sacred Scriptures as an infallible guide. Without freedom there can be no thorough education. Education, in its turn, awakens the desire for freedom. Some day it will induce both people and priests to rise and resolutely to sweep away whatever cannot be justified by a reference to the sacred canon.

And we believe in the Holy Ghost. He is the Lord and giver of life. No Christian church is so dead nor so sunk in superstition that He may not breathe upon it. We do not suppose that He can be expected to breathe upon Islam.

Cyprus, I think, we ought to keep. Our material, our imperial interests seem to require it, and, should we purchase the Sultan’s rights over it, we shall have as good a title to show as anyone to whom it ever belonged. But let us try to cement our rule there in the hearts of the people, and then we shall not, like the Venetians, have a hostile garrison within our ramparts. Let us acknowledge that three-fourths of the Cypriots are Greeks, and take a deeper interest in the Greeks for their sakes.

Notes

[1] Boeotian pig. It is worth noticing that in modern times ‘Bulgar-kephalè’ has a similar signification.

[2] Εγχειρίδιον χωρογραφίας και γενικής ιστορίας της Κύπρου υπό Ευρυβιάδου Ν. Φραγκούδη Εν Αλεξανδρεία. 1886.

[3] Marcello Cerruti served as a diplomat in Cyprus in 1841.