Σ.Ε.Κ.Α. Victoria

The Justice for Cyprus Co-ordinating Committee, Webmaster: Pavlos Andronikos

The Justice for Cyprus Co-ordinating Committee, Webmaster: Pavlos Andronikos

Compiled by Pavlos Andronikos

Judging from what has been called the “national oath” (Kıbrıs Türktür Türk kalacak, i.e., “Cyprus is Turkish, and will stay Turkish”), the underlying Turkish position with regard to Cyprus is that it should belong to Turkey. This has been unequivocally stated innumerable times by representatives of the Turkish Government, but such statements have rarely been given serious consideration by commentators and analysts,* who perhaps think they are mere bluster and exaggeration. And they may be, but it is also possible that they are not—that in the long term that is what Turkey aims for, even if her actual demands at any given time are tempered according to prevailing circumstances and what is perceived to be achievable in the short term.

In any consideration of Turkey’s position it has to be borne in mind that the population and culture of Cyprus has since ancient times been predominantly Greek, and that attitudes which regard the aspirations and ethnicity of a coveted area’s population as irrelevant should have no place in the modern post-UN-charter world.

What follows below is a small contribution to understanding Turkish involvement in the Cyprus issue. The intention is to gather in one place materials for the study of the role of Turkey in the Cyprus Issue. The collection of material and the information contained here is by no means complete yet, but we will add to it over time as material is collected.

* A noteworthy exception in this regard is the warning by the historian Christopher Walker, soon after the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974, that Cyprus may end up going the way of Alexandretta, which was swallowed up by Turkey in 1939:

“... on the precedent of Alexandretta, they might find that agreements with Turkey have a curiously fragile nature—a characteristic of the ceasefire of July 22, 1974—until, perhaps, the Republic of Cyprus becomes the Turkish province of Kibris.” (Christopher Walker, “Lessons of Turkey’s subtle land-grab,” The Times, 5 September 1974, p. 14.)

** Please note that where full bibliographical details of a source are not given here, they can be found on the Bibliography page.

To view or hide each year's entries click on the year/title.

According to a Special Branch report for August 1957 by A. F. Thomson, Chief Superintendent of Police in Cyprus, Hasan Nevzat Karagil was expelled from the UK in 1952 for agitating for the return of Cyprus to Turkey. The report contains the information that he was born in Cyprus but moved to Turkey and took out Turkish citizenship before heading for the UK. (Fanoula Argyrou, “Τούρκοι: Διχοτόμηση, η μόνη λύση,” Σημερινή [Simerini], 23 Nov. 2010.)

Telegram 5387, June 19, reported that Evangelos Averoff, Greek Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, told Peurifoy in Athens on June 18, that in his discussions with the Turkish Prime Minister and Foreign Minister during the Greek royal visit to Turkey, the Turks would not discuss Cyprus enosis [i.e., union with Greece], stating that they themselves had strong interests therein because of former possession of the island and the Turkish minority there. They assured the Greeks that they would not let the British play them off against the Greeks in discussing Cyprus. Peurifoy reported that Averoff said that if and when the Greeks secure Cyprus, they will make ample provision for the Turkish minority and will grant the British whatever bases they want on a 99-year lease. (781.11/6—1952) (Foreign Relations of the United States, 1952–1954, Volume VIII, doc. 357, p. 675, note 6)

Although Turkey has tried to dissociate itself as much as possible from agitation on the Cyprus question, it has firmly stated its intention of being heard if the status of Cyprus should change, basing its interest on the large Turkish minority in the island. (Foreign Relations of the United States, 1952–1954, Volume VIII, doc. 361: Memorandum of Conversation, by the Deputy Director of the Office of Greek, Turkish, and Iranian Affairs [Baxter], p. 680)

SECRET

897. Department’s CA-443 [4336], February 18. In conversation with Under Secretary Birgi today he raised Cyprus question on own initiative. He stated British recently approached Turks ascertain their views if Greeks should raise issue in UN. Turks replied they would consider such action by Greece most unfortunate. Turkish Government most desirous avoid involvement but if issue raised in UN will assert its interest and ask participate any Anglo-Greek discussions.

Foreign Office now informed by British Greek Government has formally advised UK its intention raise issue next UNGA. British inquired if Turks prepared support their request to US that we urge Greek Government not take this step. Turks have now decided do so and instructions to Embassy Washington going forward soon.

Briefly summarizing Turkish position, Birgi said, raise issue Cyprus union with Greece in UN would evoke sharply critical reaction in Turkey and jeopardize existing good relations with Greece. For this reason Turkish Government has been most careful avoid any action or statement on Cyprus which might inflame public opinion. No formal representation has ever been made to Greek Government although it has been intimated indirectly several times that Turkish Government hoped Greek Government would not officially support agitation for Enosis. Foreign Office now considering formal representations and Birgi thinks it likely they will be made. Turks would stress argument to raise issue in UN would benefit only common enemy. Furthermore, Arab-Asiatic bloc could be expected utilize it to maximum for own ends.

Birgi expressed personal view Kyrou may be personally active in pushing action by Greek Government since appointment as Secretary General Foreign Office because strong personal feelings on subject. He states Kyrou expelled from Cyprus by British some years ago for anti-British activities. (Foreign Relations of the United States, 1952–1954, Volume VIII, doc. 362, pp. 680-681)

The Turkish National Student Federation in Istanbul held meetings on the Cyprus issue. It was decided “to arrange exchanges between Turkish and Turkish Cypriot students in order to strengthen the ties between Turkey and the Turkish Cypriots”. (Ioannides, In Turkey’s Image p. 76)

Following Anthony Eden's announcement that British forces were to be withdrawn from the Suez Canal Zone, the Secretary of State for the Colonies Henry L. Hopkinson announced plans for a new constitution for Cyprus, which would give some representation to the populace, but not a majority to the Greek Cypriots in the legislature. On being questioned about it he replied: “In regard to the second part of the question, it has always been understood and agreed that there are certain territories in the Commonwealth which, owing to their particular circumstances, can never expect to be fully independent.” The word “never” stirred up fierce resentment in Cyprus and Greece. (Hansard House of Commons Debate, 28 July 1954, vol. 531 cc. 508)

Responding to the British plan for a new constitution, the Turkish National Student Federation issued a pamphlet stating inter alia: “It is our sacred duty to resist any action which will disturb the tranquility of the island which is an inseparable part of our own country and a sacred legacy of our grandfathers.” (Ioannides, In Turkey’s Image p. 76)

Note:The Turkish Cypriot newspaper Halkın Sesi (Voice of the People) was founded by Fazil Küçük in 1942.

From a legal as well as moral point of view, Turkey, as the initial owner of the island just before the British occupation, has a first option to Cyprus. The matter does not end there. From a worldwide political point of view as well as from geographical and strategical points of view Cyprus must be handed to Turkey if Great Britain is going to quit.

[....]

The Turkish youth in Turkey, in fact, has grown up with the idea that as soon as Great Britain leaves the island the island will automatically be taken over by the Turks. It must be clear to all concerned that Turkey cannot tolerate seeing one of her former islands, lying as it does only forty miles from her shores, handed over to a weak neighbour thousands of miles away... (From http://www.cyprus-conflict.net/Kucuk-1954.html)

Editorial Comment: It should be noted that Cyprus has never been part of Turkey or ruled by Turkey. Küçük is choosing to treat the Ottoman Empire and Turkey the nation-state as identical. His argument is nonsense. If all former Ottoman dominions were to be regarded as rightfully belonging to Turkey, then Turkey the nation-state would include the Balkans, the Middle East, and all of the Eastern Mediterranean.

The Turkish National Student Federation Executive Committee held a meeting with the newspaper owners and editors of Istanbul, where most of the national newspapers were published, to discuss Cyprus. Presiding over the meeting was the owner of the newspaper Hürriyet. It was decided at the meeting to form an association to be known as the Cyprus Is Turkish Committee (Kıbrıs Türktür Komitesi). Hasan Nevzat Karagil was elected President.

The charter of Kıbrıs Türktür stated that its aims were: “To acquaint world public opinion with the fact that Cyprus is Turkish, to defend the rights and privileges of Turks with regard to Cyprus... and to condition Turkish public opinion.” (Ioannides, In Turkey’s Image p. 77)

Within a few days of its establishment, the Executive Council of Kıbrıs Türktür was received by the Turkish Prime Minister Adnan Menderes in the Governor’s Mansion in Istanbul. Also present was Fatin Zorlu, Turkey’s Minister of State. The meeting was arranged by the editor of the newspaper Vatan Ahmed Emin. Menderes was pleased about the establishment of Kıbrıs Türktür and confided classified information to the Executive Council. (Ioannides, In Turkey’s Image p. 81)

After submitting its constitution to the Istanbul District Administration, the Kıbrıs Türktür Committee acquired legal status with the name Cyprus Is Turkish Society (Kıbrıs Türktür Cemiyeti). Hikmet Bil, the editor of Hürriyet was elected president of the now formally established organisation. (Ioannides, In Turkey’s Image p. 83)

Greece applied for the first time for Cyprus to be discussed at the United Nations General Assembly by proposing a draft resolution asking that “the principle of self-determination be applied in the case of the population of the Island of Cyprus”. That resolution was sidelined by a counter-resolution proposed by New Zealand, at Britain's behest no doubt. On 17 December the United Nations General Assembly adopted a modified version of the counter-resolution: that “for the time being it does not appear appropriate to adopt a resolution on the question of Cyprus”. (See http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/9/ares9.htm.)

Led by EOKA, the armed struggle for the liberation of Cyprus from British rule began just after midnight with a series of bomb blasts. There followed “two months of relative calm, with no further acts of violence”. (Morgan, Sweet and Bitter Island p. 212)

Winston Churchill resigned as Conservative Prime Minister of the United Kingdom due to ill health, and was replaced by Anthony Eden.

In response to leaflets circulated throughout Cyprus on 30 June calling on Turkish Cypriot youth to oppose EOKA, EOKA circulated a leaflet in Turkish explaining that its campaign was directed against British Colonialism and not against Turkish Cypriots.

“... Our intentions towards the Turkish inhabitants of the island are pure and friendly. We are looking at the Turks as our genuine friends and allies and, as far as we are concerned and to the extent it is in our power, we will not condone any harm whatsoever against their life, dignity, honor, and property...” (Ioannides, In Turkey’s Image p. 56)

“Cyprus is Turkish ... The duty of Great Britain is to give the house to the real owner and let the owner deal with the unruly subtenants. Turkey and Turks of Cyprus consider Great Britain as a nation of gentleman. They feel that, if she decides to leave Cyprus, she will invite the true owner.” (Quoted in Murat Çalişkan, The Development of Inter-Communal Fighting In Cyprus: 1948-1974 [M.Sc. International Relations Thesis, “Middle East Technical University”], December 2012)

Hikmet Bil, President of the Cyprus Is Turkish Society, arrived in Cyprus with Kamil Onal, the General Secretary. Their aim: “to assure a reaction to the cause abroad”. Following meetings with Hikmet Bil, Fazil Küçük changed the name of his party to the Cyprus Is Turkish Party. (Ioannides, In Turkey’s Image pp. 99-100)

Charles Foley: “I was given their viewpoint at a cocktail party offered by the Turkish Consul-General.

My mentors were Dr Fazil Kutchuk, the owner-editor of a newspaper, Halkin Sesi, and Mr Hikmet Bil,

who had recently come from Ankara on an important mission: to help reorganize the Turkish-Cypriots’ political party. Mr Bil

told me it was to be re-named ‘The Cyprus is Turkish Party’ which sounded original, if mildly seditious. Mr Bil explained

that it was a perfectly proper title. ‘If, and only if, Britain decides to abdicate in Cyprus, then we shall put forward

our claim to regain the island for Turkey.’ He breathed in. ‘If necessary, we shall fight.’ Dr Kutchuk, who had studied

his medicine in Lausanne and preferred to speak French, was an earnest, melancholy, middle-aged man. He said a sister

party was now being formed in Turkey itself and would soon have half a million members, all ready to back up their brothers

in Cyprus. Was this done with the approval of the Turkish Government? But naturally, nothing would be done without that.

The doctor added that he had recently received a letter ‘written in red ink’ threatening his life; as a first step his

garage would be burnt down. He defied the Greeks to touch him. His colleagues agreed that at once a hundred thousand

Turkish Cypriots would surround his dead body: a hecatomb of Greek corpses would rise! I joined them in contemplating

this vision with mournful satisfaction; soon, glowing with whisky and knowledge, I drove off.

The Cyprus Government raised no objection to the new party or its title when it was announced, and no questions were

asked of Mr Bil, a foreign national concerning himself with colonial politics. Understandably, the stronger EOKA grew,

the more indulgence was shown to the Turks. (Foley, Legacy of Strife pp. 29-30. Charles Foley was the founder of The Times of Cyprus.)

“In 1955, Dr Fazil Kuchuk was allowed to organize, with the declared help of a Turkish national named Hikmet Bil, a political party with the striking name of the ‘Cyprus Is Turkish Party’. This was at a time when all Greek parties were banned, and Britain claimed exclusive sovereignty over the island.” (Hitchens, Hostage to History p.45)

Zorlu was appointed Acting Foreign Minister and Turkey's representative to the London Conference. After his appointment “he established a small committee of experts to study the Cyprus problem. The committee included Nuri Birgi (General Secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs), who composed Turkey’s White Book on Cyprus; Rüştü Erdelhun (second-in-command of the Turkish General Staff); Settar İksel (Turkish Ambassador to Athens); Orhan Eralp (General Director of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs); and Mahmut Dikerdem.” (Vryonis 2005, pp. 81-82.)

“On 16 August 1955, Hikmet Bil... sent a letter [circular] to all branches of the KTC [Cyprus Is Turkish Society] stating the necessity of a “manly reaction” from the Turkish motherland in order to intimidate London and Athens.” (Güven, “Riots against the Non-Muslims of Turkey”).

In this circular, dated August 16, 1955, Hikmet Bil refers to a letter dated August 13, 1955, sent by the Cyprus is Turkish Party President General [sic] Dr. Fazıl Küçük to the central headquarters [of the society] in which the latter said that particularly recently the Island [i.e., Cypriot] Greeks had become intolerable and unfortunately the situation is becoming worse. If one can believe the news being spread around Nicosia, they [the Greek Cypriots] are getting ready for a general massacre [of the Turkish Cypriots] in the near future.

Küçük’s letter continued with the following:

“My request of you is that as soon as possible you inform all branches of this situation and that we get them to take

action. It seems to me that meetings in the mother country would be very useful. Because these [Cypriot Greeks] will

hold a general meeting August 28. Either on that day or after conclusion of the Tripartite Conference they will want

to attack us. As is known, they are armed and we have nothing.”

(From the transcript of the court proceedings in February 1956 against Hikmet Bil and other members of the Cyprus

Is Turkish Society. Quoted in Vryonis 2005, p. 83.)

Editorial Comment: Thus was a rumour with no basis in fact, intended “to condition Turkish public opinion”, manufactured.

... Bil transformed the general anxiety of a segment of Turkish Cypriots—and the general, non-specific information passed on to him by Fazıl Küçük and Faiz Kaymak—into a definitive, planned, general massacre of Turkish Cypriots by their Greek neighbors on August 28. There is no evidence whatsoever that such a massacre was ever planned, and it was certainly never attempted either by EOKA [National Organisation of Cypriot Fighters] or the Greek Cypriot leaders at the time. Nevertheless, through the circular and in an article that was published in Hürriyet on August 18, Bil gave the rumor of the massacre its final form, which, as such, was passed off to the Turkish people as a whole. Only two days after receiving the copy of Küçük's letter, he wrote in his newspaper that: “One can say today that the Greeks of Cyprus are fully armed. As for the Turks, they do not have weapons even for display.... In this manner there has arisen today a paradoxical situation in Cyprus. According to special information that has been transmitted to us from Cyprus, the Greeks of the island will organize a major demonstration on the twenty-eighth of the present month, and they will attack the Turks. From all this, the Greeks have also given a name to this day: They have named it ‘The day of the general massacre’....” Accordingly, from August 18, by virtue of both the circular and the article in Hürriyet, the rumor of the massacre became an established ‘fact’, and was now adopted by individuals and groups devoted to creating an atmosphere of hysterical chauvinism and passionate hatred of the Greek minority.

On the day Bil’s article appeared, the KTC’s Bandırma branch telephoned the offices of the newspaper Tercüman, which published the branch’s decision to send 1,000 KTC members to defend Turkish Cypriots, all to go before August 28. (Vryonis 2005, p. 85.)

On August 20, Tercüman published a second news item from Bandırma, according to which Menderes himself had replied to the local KTC office’s offer to send 1,000 volunteers to defend Turkish Cypriots: “I esteem your patriotic sentiments. At the same time that I express to you my respect, please remain certain that the Government is ever alert and that it shall not hesitate to take the required measures.” (Vryonis 2005, p. 86.)

... Yeni Sabah published a second statement by Faiz Kaymak: “The innocent and unarmed Turks fear that at any moment they will be massacred by the terrorists. We desire that Turkey provide every aid and that it ensure the lives and the property of the Turks of Cyprus.” (Vryonis 2005, p. 86.)

... Prime Minister Menderes held a banquet at the Liman Lokantası (Harbor Restaurant) in honor of Foreign Minister Zorlu and of the members of his mission who were to depart for London to represent Turkey at the Tripartite Conference. Among the guests were various other ministers, members of parliament, businessmen, and newspaper editors....

Menderes’ speech at the banquet included the following:

“The stance that the terrorists have taken on the question of Cyprus, and all that which is being said in regard to our subject, have plunged us into justified uneasiness. This malaise refers in part certainly also to the future. Among all these things, the major source of our malaise is constituted by all those things that are reported, somber events that will unfold in Cyprus from one day to another. We do not wish to consider these things certain, nor are we able to accept that it is possible that the matter may take such a turn. Nevertheless, those men announce uninterruptedly, with a terrorist air, that August 28 shall be a day of general massacre of our fellow Turks in Cyprus. We are certain that the British Government, based upon its legal rights, shall carry out its obligations thoroughly. It is said that the excitation of the Greek population of the island... has reached a peak. Consequently, a sudden undertaking, a criminal initiative devoid of all conscience, could provoke results of which the consequences would be inescapable and incurable... The local officials, it is possible, will be unprepared for this. And our population there will probably be found to be unarmed and unable to move against a majority which is extremely excited and armed. This does not mean, however, that these people, I mean the Turks, will remain, not even for a moment, undefended.” (Vryonis 2005, pp. 87-88.)

Editorial: Britain initiated the conference, ostensibly to discuss security issues in the Eastern Mediterranean, but with the real purpose of bringing together representatives of Greece and Turkey so that it could be made clear to the Greeks that Turkey regarded itself as an interested party in any discussions about the future of Cyprus. The conference ended in disarray with news of an anti-Greek pogrom in Turkey (mainly Istanbul, but also Izmir and Ankara). Zorlu, who had been closely involved in the planning for the pogrom, blamed the Greeks, arguing that their provocative Cyprus policy had caused the attacks. The Turkish delegation was recalled by Menderes, and left London on 8 September.

“One day before the attacks, on 5 September 1955, Prime Minister Adnan Menderes had dinner with Hikmet Bil, and told him

that he had received a ciphered telegram from the Minister of Foreign Affairs Fatin Rüştü Zorlu, who had been visiting

London for the Cyprus Conference. The Foreign Minister reported that he had faced difficulties during the negotiations,

that the terms of negotiation were hard and that during negotiations, he would like to utter Turkish public opinion to be

formed. In other words, the Minister was demanding more action from the mainland.

Bil reported this information to the executive board of the KTC, which was convened for an urgent meeting on the same

day.” (Güven,

“Riots against the Non-Muslims of Turkey”. Güven's source is an interview with Hikmet Bil, 15 Jan. 2002.)

"In September 1955, as Cyprus was being discussed at a three-power conference in London, the Turkish secret police planted a bomb at the house where Kemal Ataturk was born in Salonica. At the signal of this `Greek provocation', mobs swarmed through Istanbul looting Greek businesses, burning Orthodox churches, and attacking Greek residents. Although no one in official circles in London doubted that the pogrom was unleashed by the Turkish government, Macmillan—in charge of the talks—pointedly did not complain.” (“The Divisions of Cyprus” by Perry Anderson in London Review of Books vol. 30, no. 8, 24 April 2008, pp. 7-16.)

“On 6 September 1955 at 13.00, Turkish state radio announced that a bomb attack had taken place at the house in Thessalonica where Atatürk was born, and this news spread out with two different afternoon copies of the newspaper İstanbul Ekspres [...] which was printed in extraordinary numbers that day.” (Güven, “Riots against the Non-Muslims of Turkey”)

In the afternoon of 6 September, after news reached Istanbul of the bomb attack to Atatürk’s home, [Kâmil] Önal made the following statement to the evening copy of İstanbul Ekspres: “Eventually, we can obviously confess that we will call to account those who dared lay hands on our sacred values.” While Önal was handing out posters and copies of the İstanbul Ekspres to a crowd in front of the TMTF premises, Orhan Birgit, a member of executive board, wrote a declaration on behalf of the KTC condemning the attack on Atatürk’s home and asking the people to act in solidarity and to devote themselves to the national oath ‘Cyprus is Turkish, and will stay Turkish.’” (Güven, “Riots against the Non-Muslims of Turkey”)

The demonstrators kept chanting the slogan: “Cyprus is Turkish and will remain Turkish, Greeks are curs and will remain curs.” (Soner Yalçın & Doğan Yurdakul, Bay Pipo [Doğan Kitap, 1999] pp. 48-52. Translated from Turkish by Tim Drayton.)

In household attacks, Greek-Orthodox women in particular were raped. The Chief Physician of Balıklı Hospital reported that

60 Greek-Orthodox women were treated accordingly. [Public Record Office, Prime Minister’s Office 11834/447, Report from the

General Consulate of Istanbul, 22 Sept. 1955] If we assume that many rape victims concealed what had happened and avoided

medical care, it can be claimed that the actual number of rape victims was higher.

The number of deaths is uncertain; in the Turkish press it was reported that between 11 and 15 people died.

According to

records of the German Consulate General, economic losses amounted to approximately 150 million Turkish Liras (TL), an amount

equal to the value of 54 million US Dollars in that period. 28 million TL of this financial damage belonged to Greek citizens,

68 million TL to Greek-Orthodox citizens of the Turkish Republic, 35 million TL to churches, and 18 million TL to foreigners

and other minorities (Armenians and Jews) respectively. [Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amtes (Berlin) 9 Türkei

205-00/92.42, Report from the General Consulate of Istanbul, 11 Jan. 1956] (Güven,

“Riots against the Non-Muslims of Turkey”)

“Gökşin Sipahioğlu, the editor of the İstanbul Ekspres at that time, explained in an interview that the events of 6

September 1955 were organised by the MAH [the National Security Service]. Sipahioğlu’s account was confirmed by a brigadier

general in an interview conducted in 1991 [Milliyet 1 June 1991] regarding the structure and working principles of Special Operations:

‘The attacks of 6/7 September were certainly planned by the Special Operations Unit. It was an extremely premeditated

operation and it accomplished its objective. Let me ask you; wasn’t it an extraordinarily successful action?’ (Güven,

“Riots against the Non-Muslims of Turkey”)

In those days the young officer Sabri Yirmibeşoğlu, who rose to the rank of full general in the Turkish armed forces and held the post of general secretary in the National Security Council, was assigned to the Special War Unit, the Mobilisation Study Council.

Years later, having retired from the rank of full general, he took journalist Fatih Güllapoğlu behind the scenes of the 6-7 September events:

Yirmibeşoğlu: Then if we take the 6-7 September events...

Journalist: Sorry, commander, I don’t quite understand. The events of 6-7 September?

Yirmibeşoğlu: Of course… 6-7 September was the work of Special War [Unit] and was a splendid piece of organisation. It also achieved its aim. (I broke out in a cold sweat as the commander spoke these words.) I ask you. Was this not a splendid piece of organisation?

Journalist: Oh, yes commander!

(From: Fatih Güllapoğlu, Tanksız, Topsuz Harekat [Tekin Yayınevi, 1991] p. 104. Quoted in Soner Yalçın & Doğan Yurdakul,

Bay Pipo [Doğan Kitap, 1999] pp. 48-52.

Translated from Turkish by Tim Drayton.)

In Cyprus, the Turkish Cypriot paramilitary organisation Volkan revealed its existence with a first announcement prepared by Erdan Ali. Turgut Mustafa Özkaloğlu, a member of Volkan, remembers that the announcement used the slogan "Every Turk is a Volkan", and demanded partition, claiming that 38% of the territory of Cyprus was land owned by Turkish Cypriots. (Athanasiades, TMT p. 196; Ioannides, In Turkey’s Image p. 125)

“Though the Turkish Cypriot terrorist group Volkan was founded in 1955, and carried out many lethal attacks on civilians, very few members of it were ever tried, let alone punished by the British crown. In contrast, numerous supporters of the Greek Cypriot EOKA were hanged and hundreds more imprisoned.” (Hitchens, Hostage to History p. 46)

According to statements Rauf Denktash is reported to have made, Volkan was established by the British:

“... Mr Denktash ... said that Volkan was established by the British, that its members were British agents,

that all those who were members of Volkan were later sent by the British to Britain where they were given jobs

and many other things. That it was not really a terrorist organisation, as we know them...”

(TMT: With Blood and Fire, Part 1, Cyprus

Broadcasting Corporation, 13 January 2006)

Editorial Comment: VOLKAN means volcano but it is also an acronym for the phrase "Var Olmak Lazımsa Kan Akıtmamak Niye" which means "If existence is a necessity, to what end no bloodshed?" (See, for example, http://anamurunsesi.com/YANSAYFA/koseyazilari/u keser tmt bayraktari vuruskan.htm.)

The left-wing Turkish Cypriot weekly newspaper İnkılâpçı (Revolutionary) began publication. It would continue for only 14 weeks. After a state of emergency was declared by the colonial government, it was banned, along with AKEL’s Νέος Δημοκράτης (New Democrat). See “26 November 1955” and “12 December 1955” below.

On 24 September Cabinet decided to dismiss the Governor of Cyprus Robert Armitage. His notice of dismissal arrived on the following day. He left Cyprus on 3 October 1955. On 16 August Macmillan had written to Eden, “I am really worried about Cyprus... The real trouble is at the top. Could we not have a new Governor?” (Macmillan to Eden, 16 Aug. 1955, PREM 11/834, quoted in Holland 1998, p. 71.)

Robert Armitage left Cyprus, and Field Marshal Sir John Harding arrived to take over the position of Governor General. (See “New Stage in Cyprus Begun,” The Times, 4 October 1955, pp.8 & 16.)

... Sir John Harding sought to crush the insurgency quickly, using force. To realize this goal he recruited poorly educated and rural men from both ethnic groups on the island for the Cypriot Auxiliary Police Force (CAPF). A disproportionate number of the 1,386 men hastily recruited in 1955 were Turkish Cypriots (37 percent compared with the island’s population distribution of 18 percent), even though experienced colonial officials warned against the possible long-term effects of recruiting Turkish police. Moreover, these men were poorly trained, low-paid, and unprepared to carry out their primary purpose: to suppress the rebellion and provide support for the British military’s strategic deployments against EOKA insurgents in the rural districts of Cyprus. Facing threats of violence, poor working conditions, and EOKA pressure, Greek recruits soon left the force, so that by 1956 it became an exdusively Turkish Cypriot auxiliary force. By 1958 the CAPF had 1,594 recruits, drawn from the Turkish population and augmented by the Special Mobile Reserve, a marginally better-trained troop of 569 Turkish Cypriots devoted to riot duty only. My father was a member of the CAPF. [...] The creation of an exclusive ethnic local group to police another ethnic group was instrumental in developing and fermenting the divisions that characterize the tensions on the island today. (Gülgün Kayim, “Crossing Boundaries in Cyprus: Landscapes of Memory in the Demilitarized Zone”. In Walls, Borders, Boundaries: Spatial and Cultural Practices in Europe, eds. Marc Silberman, Karen E. Till, Janet Ward [Berghahn Books, 2012] p. 213)

Harding’s policies also led directly to the increase in communal tension, and eventually outright war between the Greeks and Turks on Cyprus. Before the insurgency Greek and Turkish Cypriots had lived in relative harmony and there had been little trouble. At the start of the insurgency, EOKA was careful to target only British personnel and facilities in order to reassure the Turks that they would be left alone, and their rights and property respected if Cyprus were united with Greece. Harding saw the Turks, who favored the status quo, as allies, and an additional source of manpower to crush EOKA. So he greatly expanded the size of the Auxiliary Police.This action went counter to the advice of experienced colonial officials, who knew that reliance upon a Turkish police force would alarm the Greek Cypriot population and likely lead to open conflict between the island’s ethnic communities—a development that the Colonial Office officials desperately wanted to avoid. Brushing such warnings aside, Harding proceeded with his plan to reinforce the security forces with Turkish auxiliaries. In 1956 the Auxiliary Police was expanded to 1,417 personnel, a larger force than the entire regular police of 1954. Harding then employed the Turkish Cypriots as a main force to suppress the insurgency, again disdaining the advice of civilian officials with long experience in Cyprus. In September 1955, a new police force was formed, the Special Mobile Reserve, which was recruited exclusively from the Turkish community. [...] Harding’s counterinsurgency strategy proved dramatically counter-productive. Deploying large numbers of untrained, undisciplined, and poorly led Turkish policemen against the Greeks guaranteed a culture of police abuse and an immediate rise in communal tension. (James S. Corum, Bad Strategies: How Major Powers Fail in Counterinsurgency [Zenith Imprint, 2008] pp. 109-111. See also Training Indigenous Forces in Counterinsurgency: A Tale of Two Insurgencies by LTC James S. Corum.)

When the armed struggle started, the British had at their disposal thousands of men and could even increase their existing numbers to put down the EOKA struggle. This they did not do, but they formed instead the well known Auxiliary Corps. The ordinary Turkish Cypriots, who did not realize where the British were leading them (since their leadership did not warn them, rather it encouraged them), hastened to reinforce this Auxiliary Corps thinking only of securing a living. Thus, the Greek Cypriots, who thought that they were waging a holy struggle against the British, found themselves facing the Turkish Cypriots. (Ibrahim Aziz, The Historical Course of the Turkish Cypriot Community, 1981)

According to Lennox-Boyd, responding to a question in the House of Commons, by 1958 there were “536 Turkish Cypriots in the mobile reserve and no Greeks, and 1,281 Turkish Cypriots and 56 Greek Cypriots in the auxiliary police.” (Hansard HC Deb 17 June 1958 vol 589 cc867)

At every opportunity, the British urged the [British] commandos and the [Turkish Cypriot] auxiliaries to maltreat the Greek

suspects in order to create a chaotic situation between the two communities. Using their puppets, they stirred up the masses.

I therefore felt the necessity many times to intervene and use my prestige in order to prevent destructive incidents which

were the aim of the British. My continuous interventions angered the British, as can be as seen from the following incident:

Late one evening, a Turkish Cypriot working for the Intelligence Service (the British Secret Service) came to my house.

As I used to be his family doctor, I thought that he or someone in his family was ill and that was the purpose of his late

visit. I said smiling: “You must have someone ill or some serious matter to come at this hour”.

My visitor seemed to hesitate to express himself. After a brief silence, he said: “Doctor, I came to ask you for something

and apologize for disturbing you at this hour. I considered it my duty to inform you that your interventions aiming at

impeding the clashes between the two communities are being watched by both the military and police authorities. Your actions

are an obstacle to their plans and I do not think it is necessary for me to tell you how much I will suffer if anything

happens to you. For this reason I ask you, whatever the case, not to intervene. This is the reason for my disturbing you

at this hour.”

I thanked my Turkish compatriot because I was certain of his sincerity. It was not news to me that the Secret Service

would not hesitate to execute me and any other person who would be an obstacle to its plans. I thought it correct to do as

my visitor advised me. Following this decision of mine, the British managed to carry out their plans in Paphos. They created

unfortunate situations between the two communities, just as they did in other parts of Cyprus. I must add that, though I

avoided intervening openly, I took every opportunity to explain to my community this sly and divisive policy of the

Colonialists. They should not have been given the opportunity to implement their malicious plans. (“Extracts from the

Memoirs of Dr Ihsan Ali”, Accessed 5 April 2013.)

A state of emergency was declared on Cyprus. (See The Canberra Times, Monday 28 November 1955.)

The last issue of the Turkish Cypriot newspaper İnkılâpçı (= Revolutionary) was published. It contained an article with the title “Threat”, revealing that the Turkish Cypriot leadership and its underground organization had sent threatening letters to the publishing team with statements like: “Cease publication or you will be killed, your head will be crushed”. (Ahmet Djavit An, “Good Old Days of Cooperation within the Working Class of Cyprus”, 2005)

Those who fell on this paternal territory entrusted you with this fatherland knowing that you would not abandon it. It is your destiny to fight for your existence under any conditions. Otherwise you are condemned to sign your own sentence. If then you too want to feel the same joy which your forebears felt when they conquered Cyprus, and to see the flag with the moon and star fluttering everywhere then prepare for sacrifices, and disregard other considerations. (Athanasiades 1998, pp. 197-8. My translation.)

Archbishop Makarios III, the political leader of the Enosis movement in Cyprus, was “kidnapped” by the Colonial authorities and exiled to Port Victoria in the Seychelles.

George Allen, the Assistant Secretary of State asked whether the Foreign Office saw any signs of a solution of the Cyprus question. Ivone Kirkpatrick, the Permanent Under-Secretary of State at the Foreign Office, said “that he was very concerned over the problem of ‘squaring the circle’, by which he meant how to reconcile Turkish and Greek interests. …

Sir Ivone continued that the Turkish point of view was not sufficiently appreciated in the United States. The plain facts were that Cyprus could not be given to Greece without provoking a war between Greece and Turkey. Sir Ivone said he wished to make it plain that he was not defending the Turkish point of view. Mr. Zorlu and Mr. Birgi [Secretary General, Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs] had taken the position at the London conference that Turkey did not want either self-determination or self-government for Cyprus and that if the British did not agree with the Turkish position, Turkey would have to reconsider its relations with Britain. Birgi had said as much right in Sir Ivone’s office and Sir Ivone had had to reply “with some acerbity”. The Turks insisted on equal representation for Turks and Greeks in any legislature that was set up in Cyprus.” (Foreign Relations of the United States, 1955–1957: Volume XXIV, Soviet Union, Eastern Mediterranean, Document 168, retrieved 2 April 2013.)

Returning from the Philippines where he had participated in the commemoration of the tenth anniversary of Filipino independence, Vice President Nixon stopped overnight in Ankara. He met with President Celal Bayar, Prime Minister Adnan Menderes, Acting Foreign Minister Etem Menderes, and Foreign Office Secretary Nuri Birgi.

On 12 July Nixon briefed the National Security Council about his trip. He referred to his visit to Turkey thus:

“Apropos of his visit to Turkey, the Vice President said that he was amazed to find that the Turks had a positively pathological attitude on the Cyprus problem. The Prime Minister had even gone so far as to suggest that if Cyprus was joined to Greece, the Turks would go to war to prevent it. He had subsequently modified this statement. The reason for Turkish alarm over Cyprus, said the Vice President, was rather the closeness of the island to the Turkish mainland than concern for the Turkish minority living on Cyprus.” (Foreign Relations of the United States, 1955–1957: Volume XXIV, Soviet Union, Eastern Mediterranean, Document 184, retrieved 2 April 2013.)

“The man in charge of British foreign policy is a Turkish gentleman, Mr Menderes.” (Randolph Churchill, “Our Turkish Foreign Secretary,” Spectator, 13 July 1956.)

Mrs. Jeger: “The Turks do not need to agitate to get their way when the Foreign Secretary does exactly as they tell him. Indeed, even a gentleman who sometimes supports the Conservative Party wrote an article in the Spectator last week entitled ‘Our Turkish Foreign Secretary’. (Hansard, House of Commons Debate, 19 July 1956, vol. 556, c1500.)

The Egyptian President, Colonel Nasser, announced the nationalisation of the Suez Canal and the Suez Canal Company.

Britain and France held secret discussions and formed a plan whereby Israel would invade Egypt, Britain and France would intervene, and in so doing would seize the Suez Canal.

Israeli forces invaded Egypt.

British and French troops launched their assault on Egypt.

Following financial and political pressure from the US, Anthony Eden, the British Prime Minister, was forced to announce a cease fire in the Suez at midnight on 6 November.

In telegram 1115, November 13, the Embassy at Ankara reported that the Turks were disturbed by reports that the United States might not oppose inscription of the Cyprus item on the agenda of the forthcoming U.N. General Assembly. The Embassy added that, in its view, inscription of the Cyprus item might endanger Greek-Turkish relations, interfere with the Holmes mission, and not serve Western interests. (Foreign Relations of the United States, 1955–1957: Volume XXIV, Soviet Union, Eastern Mediterranean, Document 209, retrieved 2 April 2013.)

Editorial Comment: Nihat Erim, who was appointed special advisor for the Cyprus issue by Prime Minister Menderes, submitted the first of two classified reports on Cyprus. (The second was submitted on 22 December 1956.) I have been unable to obtain copies of the complete reports thus far, but some scholars seem to have had access to them. Here are a few relevant quotations which give some idea of what is to be found in the reports:

Erim... argued that Turkey’s minimum policy goal should be the partition of the island (taksim). As the maximum objective he proposed the annexation and/or the strategic control of the whole of Cyprus by Turkey. As Greece’s aim was to encircle Turkey after its success in taking the Dodecanese, according to Erim, only the strategic control of the whole of Cyprus could thwart this policy objective. (Vassilis K. Fouskas, “Reflections on the Cyprus Issue and the Turkish Invasion of 1974”, Mediterranean Quarterly 12.3 [2001])

“Support for keeping Cyprus in its present form in the hands of Britain will not gain us friends at the United Nations.

The slogan in international relations since the end of the Second World War has been the abolition of colonialism. Moreover,

article 73 of the UN Charter obliges Great Britain to secure self-determination. In any case, from the beginning of the

crisis, Britain had quickly changed its stance and accepted self-determination in the form of self-government. It is not

right for Turkey, with geographical, historical and military rights on Cyprus, to argue the position that the island should

remain a British colony. When supporting this view, Turkey must state the following: the sovereignty of Cyprus should remain

with Britain with the presupposition that it must recognise the right to self-determination of its people.”

In this way, Nihat Erim attempted to align Turkey's objectives with the spirit of the time. Without modifications to

Ankara's ambitions, a position could be found that could win support for Turkey on the international stage. As for the

form of self-government supported by Ankara, there was no reason, Erim said, for that to be revealed at this juncture.

He was concerned about this, however, and in his report he examined various possibilities: “It is possible that Britain

could give Cyprus to us alone. This view has been supported from the outset by our government.”

(Costas Yennaris, From the East: Conflict and Partition in Cyprus [2003] p. 70)

According to Nihat Erim, the fact that the Turks were a small minority was inconsequential, because the

Greek Cypriot majority could be overturned: “... besides in support is the observation of the ‘father’ of the Zurich

agreement Nihat Erim, which was made in his report to the Turkish government in 1956, if you please, that ‘the Greek

majority in Cyprus is occasional [i.e., circumstantial or transitory] and may in time be overturned’.”

(My translation

from the Greek: "... σε επίρρωση άλλωστε της παρατήρησης του «πατέρα» της Ζυρίχης Νιχάτ Ερίμ, που έγινε στην έκθεσή του

προς την τουρκική κυβέρνηση το 1956 παρακαλώ, ότι «η πλειοψηφία των Ρωμιών στην Κύπρο είναι περιστασιακή και μπορεί σε

βάθος χρόνου να ανατραπεί»." Source:

“Η αχίλλειος πτέρνα των Τούρκων στο Κυπριακό” του Νεοκλη Σαρρη,

Το Παρόν της Κυριακής 17 Jan. 2010. A not entirely accurate English translation of the article is available

here.

That Turkey took seriously the security aspect of the Cyprus question was corroborated by Nihat Erim in his two classified reports on Cyprus to Prime Minister Menderes (November–December 1956). Turkey’s security is central in these reports, and is linked with the strategic balance created by the Treaty of Lausanne. (Chrysostomos Pericleous, The Cyprus Referendum: A Divided Island and the Challenge of the Annan Plan, [2009] p. 14)

Nihad Erim proposed “the geographical division of the island coupled with the transfer of populations. This straightforward proposal for ethnic cleansing would result in the formation of two separate political entities, one Greek and one Turkish, each of which would then proceed to political union with Greece and Turkey respectively.” He also proposes that “Ankara should participate in the security of the Greek sector of the island.” ( “The Cyprus Question: Historical Review”)

Four bomb explosions in Nicosia on Christmas Day are believed to have been the work of the Turkish underground organization Volkan. Three of the bombs were placed outside Greek-owned shops and houses and the fourth outside the office of the British-owned newspaper The Times of Cyprus. There was little damage beyond broken windows. It is thought that the bombs were a reprisal for the wounding of a Turkish policeman at Morphou on Sunday [23 Dec.]. (“Four Bomb Incidents,” The Times, 27 Dec. 1956, p. 5.)

On Christmas day in Nicosia, after a telephone call had accused me of ‘insulting the Turkish nation’, a bomb blew open the front door of the Times of Cyprus office. We had referred disrespectfully to partition, an idea enthusiastically adopted by Menderes and now being hammered into Turkish Cypriot heads through speeches, newspapers, and broadcasts from Ankara. Until Lennox-Boyd dropped the word, Menderes had supported British rule in Cyprus; now he said that if Turkey were not given half the island, she would take the whole. (Foley 1964, p. 89.)

Anthony Eden resigned as Prime Minister, and was replaced by Harold Macmillan. (See “Sir Anthony Eden Resigns,” The Times, January 10, 1957, p. 8. Also BBC: On This Day .)

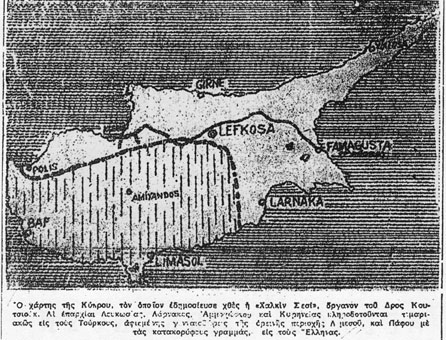

Caption: The map of Cyprus which was published yesterday by Halkin Sesi, an organ of [the party of] Dr Küçük. In feudal manner, the provinces of Nicosia, Larnaca, Famagusta, and Kyrenia are bequeathed to the Turks, generously leaving the mountainous provinces of Limassol and Paphos, marked with vertical lines, to the Greeks. (Phileleftheros, 20 January 1957. Translation: Π.Α.)

A Turkish mob set fire to-night to Greek-owned buildings in the Old Town of Nicosia, and there has been some stoning of premises. A timber store is burning fiercely, but other fires have been put out. Church bells rang to call the Greeks to action, but there have been no major clashes between Greeks and Turks... The fires... are thought to have been a reprisal for the death in a bomb explosion in Nicosia yesterday of a Turkish policeman; three other Turkish policemen were wounded. The dead man, who was 44, had six children.

After the bomb incident, Dr. Fazil Kutchuk, leader of the “Cyprus is Turkish” Party, appealed to the Turks to exercise restraint. He told a crowd of several thousand cheering people that Cyprus would have to be partitioned if the British Government rejected Turkey’s proposals put forward in answer to the Radcliffe constitution.

Dr. Kutchuk has returned from Ankara after three weeks’ stay there, and was accompanied by Professor Nihat Erim... and Mr. Suat Bilge, who are going to London for further consultations with the British Government... (“Turkish Mob Fire Greek Property,” The Times, 21 January 1957, p. 6.)

The Old Town of Nicosia was placed under full curfew to-night. Military police warned Britons to leave the Old Town immediately because of clashes between Greeks and Turks. (Reuter, 20 January 1957.)

No fewer than 70 fires were started in Nicosia yesterday, according to the chief of the fire brigade, and five of them developed into major outbreaks. [...]

In all cases the police or military were able to disperse the demonstrators quickly. There was some stoning of shop windows and vehicles, and four persons were slightly injured. Two Greek Cypriots were hurt when a policeman’s gun went off accidentally. [!]

[...] The funeral of the Turkish policeman the murder of whom in a bomb explosion had inflamed the Turks and started an outbreak of arson took place quietly this afternoon. Several thousand Turks followed the procession to the cemetery.

[...] Two bombs found in the grounds of the Phaneromeni school in Nicosia were detonated on the spot by troops. [!] (“Night of Arson in Nicosia,” The Times, 22 January 1957, p. 6.)

A new slogan was coined: ‘Turks and Greeks cannot live together’, and to prove it came a series of Turkish riots. The first outbreak followed the death of an Auxiliary policeman in a bomb attack. Although Eoka had orders not to attack Turks, it was difficult to distinguish between an armed British policeman and a Turk wearing identical dark-blue uniform; by night it was impossible. Mobs swarmed through the empty Sunday streets firing houses and shops and beating any Greek they could find. The Government seemed inert. It was twelve hours before a curfew was imposed. Most of the few Turks arrested were soon released and none was put on trial. The riots continued. There was a particularly savage one after the death of another Auxiliary in Famagusta, during which the hospital and a clinic were attacked. It seemed probable that the Greeks would retaliate before long, however much it might help the partition cause... (Foley 1964, p. 89.)

Dr. Kutchuk, leader of the Turkish community in Cyprus, has sent a message to Mr. Macmillan protesting against the behaviour of the Greek Cypriots during the recent communal strife. He said the Turks had acted with dignity and moderation under provocation. The message was also sent to Mr. Hammarskjöld, Secretary-General of the United Nations. Earlier it was announced that Dr. Dervis, the Greek mayor of Nicosia, had also sent a protest to Mr. Macmillan on the events of the past two days. (Associated Press, 22 January 1957.)

Editorial Comment: Notice the difference in the way the two sides are presented, and the failure to correct Kutchuk's blatant misrepresentation of what has been taking place. The provocation has been mostly on the Turkish Cypriot side, but Kutchuk is quoted at some length complaining about the "behaviour of the Greek Cypriots" and praising the Turkish Cypriots.

The tragic deterioration of relations between Turks and Greeks in Cyprus... is causing the gravest concern [...]

Greek Cypriots complain that Turkish auxiliary policemen did nothing to check the excesses of their fellow-countrymen and they allege, certainly unjustifiably, that the Cyprus Government turns a blind eye to misdeeds of Turks while it stamps on Greek Cypriot offenders with unrelenting severity. Cases are cited of Greeks being shot by Turkish police, the latest being at Lyssi, where a Greek was shot dead, allegedly by two Turkish policemen, while another escaped with his life by shamming dead. The Greek story is that he took the numbers of his attackers.

The official version of the Lyssi affair is that two unknown men stopped two Greek Cypriots near the village of Vatili, ordered them into a car, and drove to a wood, where they shot them, leaving one dead and one wounded. The wounded man was unable to give any detailed description, but it is certain that no Turk was involved.

The truth is that Greek Cypriots no longer have confidence that the British administration is impartial between Greeks and Turks... (“Greek-Turk Tension In Cyprus,” The Times, 23 January 1957, p. 8.)

Professor Nihat Erim, chairman of the Turkish committee entrusted with the task of examining the Radcliffe proposals for Cyprus self-government, is leaving to-day for London. It is expected that he will meet Lord Radcliffe to offer suggestions for ensuring the protection of the rights of the Turkish minority in Cyprus. Professor Erim has just been to Cyprus, where he called on Sir John Harding, the Governor, and had discussions with prominent members of the Turkish minority. (“Turkish Delegate For London,” The Times, 25 January 1957, p. 8.)

Archbishop Makarios III was “released from exile on condition that he should not return to Cyprus. He and his fellow Cypriots left Seychelles on April 5, 1957 on board the Greek Tanker Olympic Thunder, after 13 months in exile.” (“50th Anniversary of the landing of Archbishop Makarios in Seychelles”, Seychelles Nation 14 March 2006.)

“In releasing Makarios, the British Cabinet had presumed on Turkish tolerance, but simultaneously provided assurances to Menderes and Zorlu that it did not prejudice the understanding over partition that had been reached with Lennox-Boyd...” (Britain and the Revolt in Cyprus, 1954-1959 by Robert Holland [OUP, 1998], p.193.)

At a party congress in Edirne, Turkey, the Secretary General of the CHP party Kasim Gülek expressed the hope that “this Democratic Party administration will solve the Cyprus problem as the R.P.P. [CHP] administration solved the Hatay problem”. It was an election year and the opposition was spurring the Menderes government to take an even more proactive stance on Cyprus, by following Atatürk’s example in Alexandretta [renamed Hatay by Atatürk]. (See Mogens Pelt, Military Intervention and a Crisis Democracy in Turkey: The Menderes Era and Its Demise [I. B. Tauris, 2014], p. 110.)

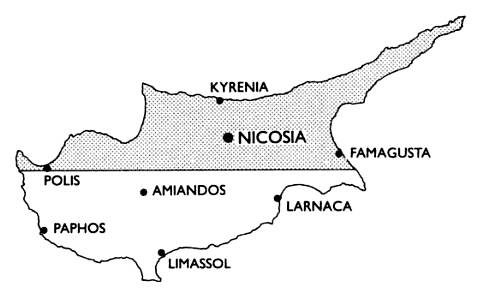

NICOSIA, July 24.—Dr. Fazil Kutchuk, the Turkish Cypriot leader, who returned from Ankara yesterday, said to-day that Turkey would claim the section of Cyprus north of the thirty-fifth parallel—about half the island—as the Turkish share under partition. It is the first time he has specified a dividing line for partition. He repeated that Turkey would insist on partition as a solution for the Cyprus problem... Dr. Kutchuk said it was a great sacrifice for Turkey to accept partition, as she had a right to claim the whole island—and she would do so if the partition proposal was not implemented. It was "too late" now to discuss the Radcliffe constitution offered by Britain, and Turkey had officially notified the British Government that in her view partition was the only possible solution. Similar notification had been given by Turkey to the United States, he said. (“Cyprus Partition Demand”, The Times, 25 July 1957, p. 10)

The same edition of the Times carried a shrewd riposte from C. M. Woodhouse on the following page:

Sir, —The leader of the “Cyprus is Turkish” association of Cyprus is reported on July 19 to have emphasized that “Turkish Cypriots, having the full support of the Turkish Government, were more than ever insistent on partition of the island.” But surely if they believe that “Cyprus is Turkish,” partition should be an utterly intolerable prospect to them, as it is to the Greeks? It might be worth reminding them, in their own interests, that the last time a comparable situation arose, it was settled by the Judgment of Solomon.

Next month Kutchuk went to Turkey again, returning to Cyprus with a Turkish newspaper columnist. They were met by a crowd of several thousands, and cries of ‘Taxim’ mingled with the bleating of a sacrificial sheep. Kutchuk said he had talked to Menderes and now he would like to see Cyprus partitioned along the 35th parallel, a considerable advance on the last claim. (Foley 1964, p. 100.)

Editorial Comment: The Cyprus is Turkish Party published a 47 page pamphlet by Fazil Kuchuk with the title The Cyprus Question. A Permanent Solution. On the cover was a map of Cyprus partitioned along the 35th parallel. (Illustration from Hitchens 1997, p. 10.) In Kuchuk’s “permanent solution”, the minority population of 18% gets half of the island, the three most important cities, including the capital, and the lion’s share of the fertile plains and coastline. In order for the Turkish Cypriots to acquire this most generous half, many thousands more Greek Cypriots would have to be relocated than the total number of Turkish Cypriots on the island.

A Special Branch report for August 1957 by A. F. Thomson, Chief Superintendent of Police in Cyprus, records that Hasan Nevzat Karagil, a lawyer and the General Secretary of the Turkish Cypriot Cultural League [Kıbrıs Türk Kültür Derneği] in Istanbul, arrived in Cyprus ostensibly to visit his parents in the Famagusta region. He was allowed into Cyprus on a 3 month visa but, the report notes, is unlikely to avoid political activities. This is the same Hasan Nevzat Karagil who was expelled from the UK in 1952 for agitating for the return of Cyprus to Turkey. (Fanoula Argyrou, “Τούρκοι: Διχοτόμηση, η μόνη λύση,” Σημερινή [Simerini], 23 Nov. 2010.)

Nevzat Karagil would be defence counsel representing the former Foreign Minister, Mr. Fatin Zorlu, in the Yassiada trials of 1960. (“Bomb Delivered To British”, The Times, November 10, 1960, Page 9.)

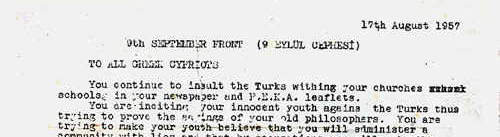

“When half of this island becomes Turkish, we will give you the same prosperity as given to the greeks of Istanbul.” (From a leaflet claiming to be from the 9th September Front [9 Eylül Cephesi] and addressed to all Greek Cypriots.)

Editorial Comment:

The organisation 9th September Front was founded by Ulus Ülfet. Ironically, he was killed a few weeks later making

bombs, in the incident of 1 September 1957 (see below). (Sources: Athanasiades 1998, p. 50; Argyrou 2009, p. 252.)

The 9th of September was the day on which Turkish troops entered Smyrna (Izmir) in 1922, following the defeat of the

Greek army at the Battle of Dumlupınar. For Turks it marks a high point in the Turkish War of Independence, a war waged against

the Allies after Asia Minor was occupied following the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in the 1st World War. It was the

Turkish War of Independence which led to the creation of Turkey the nation state.

The Greeks of Istanbul were a minority community that existed in

Turkey on sufferance, so the promise being made here contains the implication that the Greek Cypriots—the majority indigenous

population of the island—will also exist in Cyprus on sufferance. Also implied is the idea that when the island is partitioned

the Turkish Cypriots will once again be a ruling minority as they were during the period of Ottoman rule, with the power to grant or

withhold.

The Greeks of Istanbul may have once been prosperous, but, as outlined above, in 1955 they were subjected to an attack

by Turkish mobs, which was secretly organised by the Turkish Government. It was an attack from which the community was

never allowed to recover, and which marked the beginning of a rapid decline as one repressive measure followed another.

(See “Greek community in Turkey fears for its survival”, by

Jonathan Head, 7 January 2011.)

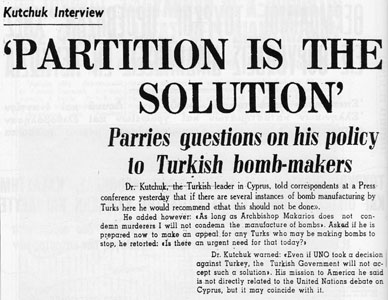

Three Turks [bomb-makers] were seriously wounded and one killed by a bomb explosion early to-day at a Turkish house in the village of Omorfita, just outside Nicosia. The incident has given rise to a belief that some Turkish Cypriots are dabbling with explosives for use against Greeks should the Eoka terrorists become active again. One of the men said they were examining an object which they had found outside the house when it exploded. A police spokesman said bombs were found inside the house. (The Times, 2 September 1957, p. 6.)

And when in 1958 the Turkish Cypriot teacher Sevim Ülfet found herself face to face with Denktash, in Nalbantoglu’s clinic which was full off dead and wounded (She too had been burnt by death because her brother Ulus Ülfet had just been blown up in Kaimakli by a bomb he was making to use against the Greeks.), she said to Denktash, “For God’s sake, order the killings to stop at last.” He replied as follows: “These dead are useful to us. With them we will make our voice be heard in the world.” (Arif Hasan Tahsin, Η άνοδος του Ντενκτάς στην κορυφή, μετάφραση Θανάσης Χαρανάς [Nicosia: Αρχείο, 2001], p. 51. My translation.)

Next month Kutchuk went to Turkey again, returning to Cyprus with a Turkish newspaper columnist. They were met by a crowd of several thousands, and cries of ‘Taxim’ mingled with the bleating of a sacrificial sheep. Kutchuk said he had talked to Menderes and now he would like to see Cyprus partitioned along the 35th parallel, a considerable advance on the last claim. The Istanbul newspaperman soon found that ‘countless barbarities’ were being practised on Turkish-Cypriots, whose women and children were regularly assaulted by savage Greeks. Although Government House described the reports as ‘fabricated’ they continued unabated into September, until one Sunday morning there came a rumour of an explosion in the suburb of Omorphita. We went to investigate.

Driving down the long, broad bypass road we could see from half a mile away the familiar signs of an ‘incident’. The black police trucks, the soldiers standing over them with rifles at the ready, the bunch of plain-clothes police in the garden. But the atmosphere was unusual. There were no angry faces, no people up against the wall for a search. I asked what had happened.

‘Turkish blokes blew themselves up,’ a soldier said.

A room at the back of the house was filled with torn bedding and smashed chairs. Bits of wreckage floated in pools of water left by the fire-hoses, for the explosion had set the house ablaze. A chest-expander hung down from the wall beside a picture of Doris Day. On the other side was a sketch of Kemal Ataturk. There was blood on the bedding. The policeman said they had found sixteen more bombs hidden in a rabbit hutch outside. One man was killed outright but another three lingered on for some days, horribly burned and mutilated. They were given a patriotic funeral, with Turkish flags, speeches, and much weeping.

Obviously the amateur bomb-makers were only part of a larger organization. Soon Turkish leaflets appeared, ordering their

own people to have no dealings with the Greeks; others threatened to destroy Greek property. ‘Partition or death’ was their

refrain. (Foley 1964, pp. 100-101.)

“The favourite rumour of 1957 came true on October 9 when it was announced that Sir John Harding was to go: he had asked to be relieved of the Governorship and Whitehall had ‘reluctantly agreed’ .” (Charles Foley, Island in Revolt [Longmans, 1962], p. 159.)

Rumors continue that Turkish Cypriots may be building up secret arms caches. Although leaders in Athens and among the Greek Cypriots have previously accused the Turks on the mainland of supplying these weapons, the Turkish newspapers have only recently indicated that these accusations may be true. Whereas few incidents between Turkish and Greek Cypriots occurred during previous periods of violence, dangerous intercommunal strife is likely if the Greek Cypriot extremists again engage in widespread acts of terrorism. (Current Intelligence Weekly Summary, CIA, 17 October 1957 [DOC_0000621950.pdf].)

The Colonial Office officially announced that Sir Hugh Foot would succeed Field-Marshal Sir John Harding as Governor and Commander-in-Chief of Cyprus, and that he would take up his new duties around the 1st of December. (“Reasons for Change in Cyprus Governorship,” The Times, 22 October 1957, p. 7.)

According to the Times, “Dr. Kutchuk... struck an ominous note in suggesting that [....] possible relaxation of emergency measures and the return of Archbishop Makarios would ‘encourage and provoke the Greeks to show hatred to the Turks,’ who would not sit idle in the face of attack.” (“Misgivings About New Era,” The Times, 22 October 1957, p. 7.)

Note: It had already been reported in the Times (19 October) that news of the appointment of Sir Hugh Foot to succeed Harding as Governor “had reached London from Jamaica”. Strangely, the same report incorporated a mention of the Greek Government’s complaints to the European Commission for Human Rights regarding the British authorities’ use of torture and ill-treatment in Cyprus; and of the news that visas had been requested for members of the ECHR to go to Cyprus and investigate. (“Governor of Cyprus,” The Times, 19 October 1957, p. 6.)

Could it be that Harding’s imminent departure from the island was linked to the ECHR investigation?

Leaflets circulated overnight in the main towns of Cyprus have announced the formation of a “Turkish resistance organization”

to protect the island’s Turkish community “against any kind of attacks.” The new organization, known as “T.M.T.” replaces the

Volkan, a smaller Turkish underground organization.

Headed “Bulletin Number One,” the leaflets called on every Cypriot Turk to “stand by for our instructions.”

(Reuter, The Times, 30 November 1957)

Note: TMT is an acronym for Türk Mukavemet Teşkilatı, i.e., Turkish Resistance Organisation.

According to Rauf Denktash, the TMT was founded by three people: the Administrative Attaché of the Turkish Consulate Kemal Tanrisevdi, Burhan Nalbantoglu, and himself. (Kibris 16 June 2000. Cited in “Denktash: Three people established the TMT”.)

Elsewhere Denktash has stated:

“... the TMT was established ... for distributing the leaflets, for neutralizing ‘Volkan’ at the beginning, until Turkey took it over.” (Costas Yennaris interview with Rauf Denktash, Nicosia, 14 February 2001. Broadcast on CyBC TV, March 8.)

“I had set up the TMT (Turkish resistance movement) with a few friends to organize the individuals who were rushing around

doing things.”

“When the TMT issued its first pamphlet, taking over from its predecessor, Volkan, Dr Kutcuk asked who these fools were.

We had not told him about TMT. He was happy with Volkan. He never got out of the feeling that he was left out of it.”

“For a few years he was most uncomfortable about it. But he trusted me and if he had any worries he would come to me and

I would placate him. We did not allow TMT to become an underground terrorist organization.”

... “Eventually TMT became more than a military

force, it became a moral force. Everybody thought I was the leader but I was not. I was political adviser. Immediately

after forming it I handed it over. It was a good mask because even the British and American intelligence thought I was

the man who ran and decided everything. I was not.” The leaders, he said, were former army officers from Turkey.

(“The politics of resistance that divided Greek from Turk,” The Times 20 January 1978, p. 17.)

Editorial Comment:

One has to wonder just what is meant by the statement: “We did not allow TMT to become an underground terrorist

organization.” In the period from May to July 1958—before the handover of the TMT to Turkish Army officers—at least six

Turkish Cypriots who disagreed with TMT’s policies and were in favour of Greek-Turkish cooperation in Cyprus were targeted

for assassination. Only two survived the assassination attempts. Moreover the period between the founding of the TMT and

its handover to Colonel Rıza Vuruşkan was one of the bloodiest in terms of violent intercommunal clashes—clashes initiated

by Turkish Cypriots who presumably had “stood by for instructions” and were now following orders.

Also questionable is Denktash’s statement that after the handover, the leaders “were former army officers from Turkey”.

If he is referring to the handover to Colonel Vuruşkan, the statement is not true. Vuruşkan and his companions were serving

officers of the Turkish Army seconded to the TMT, and the handover did not happen “immediately”.

The TMT was very active for eight months prior to being “handed over”. If Denktash was not the leader during the bloody

months of January to July 1958, who was? Or, to rephrase the question, who was responsible for unleashing the indiscriminate

violence of the intercommunal clashes?

“In the old days, there was fear of the Organization. The TMT had spread fear, so that the Turkish-Cypriots would obey them. The TMT threatened people, killed many. Often the TMT didn’t even hide that they were behind the murder of Turkish-Cypriots. Otherwise, if they hadn’t spread this terror, they wouldn’t have been able to make people submit to their authority.” (Ahmet Bey, a former member of the TMT. Quoted in Yashin 2009, p. 108.)

The new Governor Sir Hugh Foot arrived in Cyprus.

“I come with an open mind and no prejudice. We can together find a way out of our anxieties and perplexities. I am sure nothing but disaster can come if we neglect the opportunity now before us.” (“Opportunity In Cyprus”, The Times, 4 December 1957, p. 10.)

Three Turks aged 60, 25, and 40 were found murdered in a forest near Paphos. They were from the village of Melandra, and were in the area of Abdoullina to work on an irrigation project. It is not known who was responsible. It is believed they were killed with an axe. (“Three Turkish Cypriots Murdered”, The Times, December 6, 1957, p. 10.)

Editorial Comment: The report speculates that the murders may have been connected with a village vendetta, and dismisses the possibility that it was an Eoka killing, without mentioning that EOKA had called a truce in order to give the new Governor a chance, and that it did not, as a rule, target Turkish Cypriots. The possibility that it was a TMT killing is not considered.

The Governor urged the latter [Dr Kucuk] on 9 December to avoid any provocative responses, whilst his deputy, George Sinclair, who was also present, reminded the Turkish-Cypriot leader of their close cooperation during Harding’s time, and reiterated ‘the requirements of the close alliance existing between HMG and the Turkish Government’. Such talk of ‘alliance’ illustrated an increasingly desperate attempt to keep the Turks on board. Kucuk’s reply—that his community always followed instructions sent from Ankara, [my emphasis] and that so far at least these had not extended to doing anything to undermine the British presence—was by no means wholly reassuring. [Holland's source: Minutes of Governor’s meeting with Dr Kucuk, 9 Dec. 1957, C0926/643.]

The following day the meaning of Kucuk’s qualification was made plainer. A disturbance broke out around the Pancyprian Gymnasium. It was like old times, with Greek youths shouting slogans, burning Union flags and lobbing missiles at the Police. Yet whereas in the past during such riots the Turks had gone about their usual business inside their own quarter, on this occasion—whipped up by news that a Turkish policeman had been wounded—a Muslim crowd gathered and proceeded to cross into the Greek zone, smashing and burning several shops as they went. The Security Forces rushed to close the communal boundary with barbed wire, but not before several hundred had been hurt. Nicosia was curfewed for the first time for months, and there were smaller outbreaks in other towns. [....]

For the first time, Consul Belcher told Washington, the inter-communal tension had escalated into ‘a very dangerous factor’. He also passed on the reports coming into his consulate that amidst the hubbub British officers had experienced great difficulty in restraining Turkish Auxiliaries from using excessive force in dealing with demonstrators. [Belcher, telegram, 9 Dec. 1957, RG59, State Department Records, Box 3282, USNA.] (Holland 1998, pp.219-220.)

An English journalist was shot at by two Turks outside the offices of the Cyprus Mail, of which he is assistant editor. He escaped injury... (“Nicosia School Stormed”, The Times, December 11, 1957, p. 10.)

... a Turkish policeman was shot by a Greek. Though he was not seriously injured a report spread in the Turkish quarter that he had been killed. Angry Turks gathered in Ataturk Square and, advancing towards the Greek quarter, began to wreak vengeance on Greek shopkeepers and others. Two lorries were overturned and set on fire, windows were smashed, and shots fired at random into the air. Eventually the police brought the situation under control. (“Nicosia School Stormed”, The Times, December 11, 1957, p. 10.)

Editorial Comment: At that time EOKA had called a truce in order to give the new Governor a chance, so it is unlikely that an EOKA man would have been at a rally armed with a gun. It is also unlikely that any Greek not in Eoka would have used a firearm at a demonstration: the death penalty was mandatory for such an offence. Charles Foley reveals what actually happened:

His [the new Governor's] first test came with the U.N. debate. An Eoka leaflet ordered the usual one-day strike, which meant a flag-waving march to the Greek Consulate. Trouble might have been avoided, that year, if a peaceful procession through the Greek sector had been allowed by way of a goodwill gesture. But Foot’s officials had said the demonstrators might turn into the Turkish quarter and so no risks could be taken. He had to show faith in his Security experts.

The result was that by the end of the morning some forty police and troops as well as one hundred students had been injured. One of the casualties was a Turkish policeman who had been shot in the buttocks. In revenge, a crowd of 500 Turkish youths crossed the unguarded Mason-Dixon line and created the customary havoc, wrecking, looting, and burning, while Turkish Cypriot leaders protested against ‘the murder of our policeman’. A cable to Menderes declaring that every Turkish village faced a massacre was followed by a formal protest to Britain. The injured policeman (officially said to be ‘comfortable’ in hospital) was found to have been accidentally shot by a colleague while they were pursuing the same Greek schoolboy, but this fact the authorities unaccountably failed to publish. (Foley 1964, pp. 106-7.)

Last night fire gutted the offices of the Greek newspaper Alithia, and police are investigating reports that the fire had been caused by an explosion. The editor of Alithia alleged last night that he had received threatening letters in Turkish. (“Cypriot Rioter Killed”, The Times, December 16, 1957, p. 8.)

Forensic experts have completed an examination of the gutted building of the newspaper Alithia which was destroyed by fire on Saturday night. Arson had been widely suspected but the official verdict is that there is no evidence to support this. (“Cyprus Convoy Attacked”, The Times, December 18, 1957, p. 6.)

“Three Greek Cypriots were murdered by masked men in Cyprus to-day.” Vassilis Michael was beaten to death in the village of Ayios Ambrosios; Andreas Epiphaniol was stabbed outside his home near Famagusta; and “in the west Cyprus village of Loutros, a chauffeur, Christodoulos Solomiou. aged 40, was hacked to death with axes while he was in bed.” (“Risks Worth Taking in Cyprus”, The Times, 27 December 1957, p. 5.)

The authorities announced that Vassilis Michael was “in fact gravely injured, but was ‘making progress’ in hospital... Inquiries showed there was no political motive in either case.” (“Discussions with Cyprus Turks”, The Times, 28 December 1957, p. 5.)

Editorial Comment: Noting the use of axes, and the geographical proximity, one wonders if the third murder, which is not mentioned in the follow up report, was linked to the murders of 5 December 1957.

Kuchuk and the Turkish Consul-General at Nicosia were called to Ankara for consultations. Kuchuk was “received by the Turkish Foreign Minister, and reported to him on the present situation in the island.” (The Times, 31 December 1957, p. 5; and 2 December 1957, p. 8.)

Editorial Comment: Turkey was worried about the new Governor Sir Hugh Foot, who was reputed to be a liberal, and also by the possibility that the Labour party would win power at the next elections in the UK. Presumably the TMT, and the tactics to be followed while the Baghdad Pact Meeting in Ankara on 27-30 January 1958 was taking place were also topics of conversation. On the other hand it is equally likely that the Consul-General and Kuchuk, who did not return to Cyprus until the 3rd of February, were called to Turkey to get them out of the way, and give Denktash, Tanrisevdi, and the TMT a free hand. In comparison to Kuchuk, Denktash was a far more ruthless leader.